SILVIA PRADA

Text by Michael Bullock

Art by Silvia Prada

TOM, Published by Capricious

In collaboration with the

TOM OF FINLAND, FEMINIST?! SILVIA PRADA, GAY FAN BOY?!

The concept of manhood in most societies is defined (and measured) by the ability to dominate, whether it’s in sports, business, or sex. To be born with a penis but give up one’s status as a dominator is to be a traitor against one’s gender and against nature itself. For this ideology to resonate, one would have already bought into the idea that women hold a secondary status. By that standard homophobia is the anxiety-ridden stepchild of misogyny, centered on the fear men have of their potential to be feminized. The derogatory meaning of passivity in our society is continually present in our language today. It’s seen in the way we praise men who penetrate multiple women as “studs” but shame women who get penetrated by multiple men as “sluts.” Or in the negative ways we use the word fuck. “He fucked you over,” “I’m going to fuck you up” in these aggressions to be fucked is presented as a punishment, to be taken advantage of, and ultimately to be weaker than the fucker. So, the ultimate treason against masculinity is for a man to participate in sex as a passive partner. “The Bottom” spits in the face of society’s contempt and finds joy, pleasure and satisfaction in his so-called domination. On the flip side, the active partner, “The Top” should be revered. As the dominator of dominators his rightful place is at the top of this macho hierarchy but instead he evokes fear because he has the power to rob a man of his status by subjecting him to a woman’s sexual role. The male homophobe’s psychology is a two-part condition made up of disdain and anxiety: disdain for all receptive partners (be it women or men) as less-than, and anxiety caused by the active partner because they present the threat of being dominated, or worse, confront them with the prospect that they could enjoy that domination.

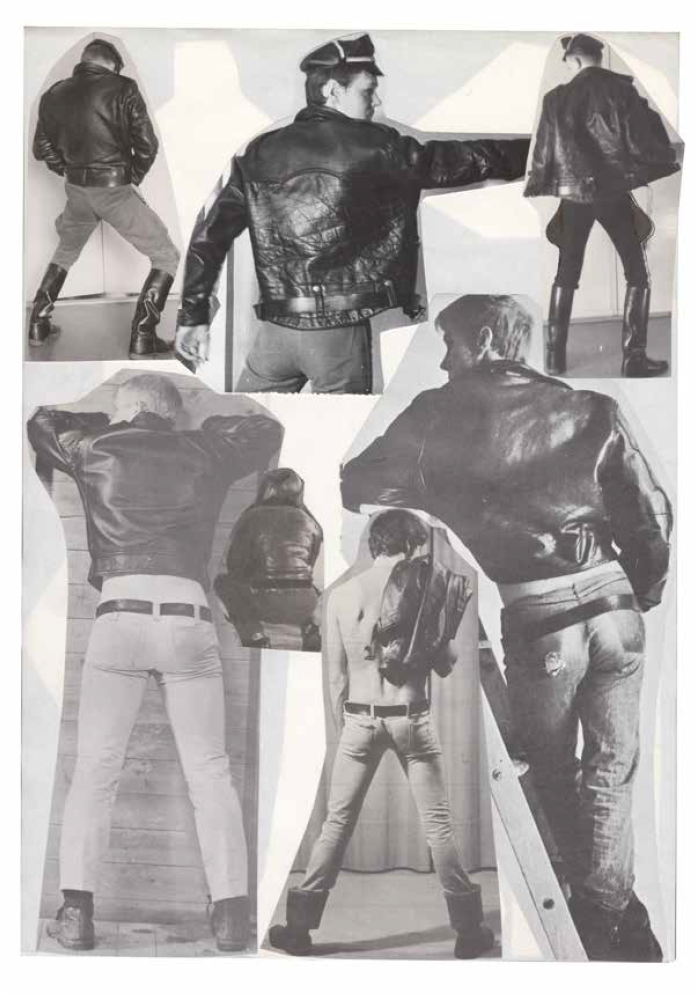

I have laid out the basics of homophobia and its roots in misogyny to think about Tom of Finland’s project in different terms. While the initial impulse for his work was a need to satiate his own sexual fantasy, it was immediately intertwined with a political mission: to deconstruct the negative clichés society associates with gay men, by making imagery that aimed to eradicate homophobia’s horrific impact on their self-esteem.By doing so he could liberate himself and his gay peers from what he called “the pathetic plight of the homosexual.” Taking a step back to the beginning of his career, there was Touko Laaksonen, the young advertising man in post-war Finland. I had never given much thought to Tom’s day job. At best, I had considered it an inconvenience, a source of income for his work as an artist. But looking through the source material as presented in this book, I began to understand how meticulous he was in finding the perfect character, expression, smile and pose to communicate the desired effect. He was considered a master draftsman but this obvious talent may have blinded us to equal areas of his genius: as a curator of human expression. It’s clear that his advertising career deeply informed his personal work giving him years of practice at composing images in service of selling ideas and products to the mass market. It’s unheard of to label Tom of Finland as a pop artist, but from this perspective, it’s not a stretch. Just as Warhol and Lichtenstein did, Tom adopted the strategies of image making from advertising to create his own work. By day Touko created campaigns that sold soft drinks, appliances and candy to the Finnish people. By night Tom of Finland worked on his lifelong advertising campaign, rebranding homosexuality to sell a joyful vision of gay sex to gay men. If his campaign were to have received a client brief, its objective would have been to dismantle homophobia. Not to change the minds of the homophobes but to ensure that their options to make gay men feel shame for what they desired would no longer be effective. His campaign would need to destroy the idea that gay men were weak by depicting more honestly the fulfilling roles that both passive and dominant partners enjoy during sex. Tom’s strategies to solve these conceptual problems were deceptively simple and extremely consistent. They could be broken down in four simple points:

1) Show naked men in nature, in daylight (refusing to hide in darkness), thus making the link that they are part of nature and that their acts are natural.

2) Depict the men as physically strong, so their muscular bodies are the embodiment of masculine pride.

3) Depict sex partners as equals by pioneering a clone look, so both dominant and submissive roles are indistinguishable and interchangeable. Tom’s men (with very little exception) are confident grown adults that are always both at once object and objectifier.

4) Reintroduce the authority figure, so whether it’s police or military officers, the men in charge of keeping the moral authority are now encouraging in and participating in the fun.

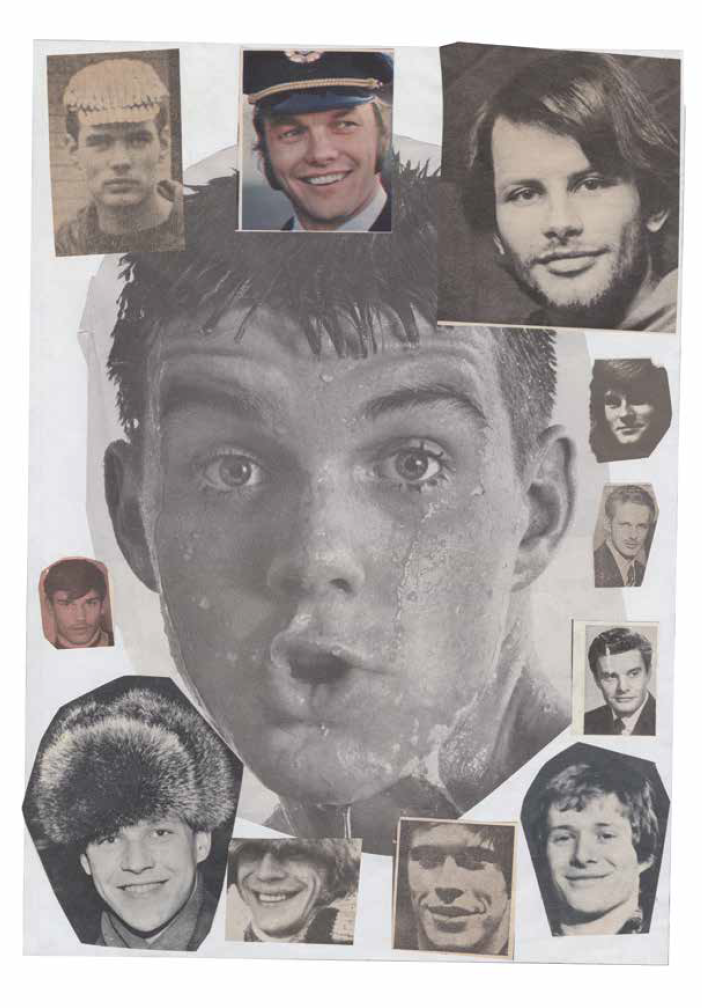

The rest, as they say, is history, or gay history. Tom’s art gave his community a road map to his vision of utopia, and once exposed to it, it would be much harder for gay mento go back to living in fear, darkness or shame. His imagery is so real, so abundant and so widely distributed, that his powerful vision of homosexual sex dominated reality, making it submit to his vision. His campaign succeeded in demonstrating sexual equality and elevating passive sexuality from a place of disdain to a place of envy. It may be unnecessary to ask my title question, is Tom of Finland a feminist? But by showcasing pride in all forms of sexual desire, by showing equality and partnership and balance within sexual relationships, he demonstrated a model of pleasure that could be consumed, learned and appropriated no matter who is participating in the sex. Fast forward to the town of León in northern Spain in the late 1980s. A teenage Silvia Prada’s identity was beginning to take form in the most unlikely place: her father’s salon for men. There she received an education in men’s style that developed into a fetishistic obsession with male beauty.“My dad wasn’t gay himself but through the salon I was exposed to gay culture.” That could all seem normal enough, but parallel to this, Silvia was coming to terms with her attraction to women. This complicated configuration—her position as an outsider with neither a place in the straight world, nor the traditional lesbian community—could have been lonely and traumatic, but it forced the resourceful budding artist to take the opportunity to forge her own path. Through exposure to the hair salon’s waiting room magazines, Silvia became an obsessive super-fan of pop culture imagery. Thirsty for more, she imported international magazines The Face, I–D, and Interview following every new development in music, film and fashion. She studied all the identities popular culture offered and made collages of the stars and styles that she felt best connected to her own sensibilities. Like many of her generation, Silvia became obsessed with George Michael and Madonna but was seduced mostly by their ability to utilize the full spectrum of gender expression. “For me, in that period pop culture was gay culture, they were one and the same.” For Silvia, pop culture was a nurturing life force. Like her heroes before her, her definition of sex appeal came to be defined as someone who embodies the full range of masculine and feminine energies: an ability that she found most present in gay men. “I don’t have any information on lesbian culture, I never connected with that. I grew up in a different way. I have never gone to lesbian bars. I met all my girlfriends at either university or male gay bars, I’m a different kind of girl, I was socialized as a fag.”

So when the 17-year-old came across a Tom of Finland article in Interview magazine she was primed for an immediate, deep connection. Even though Tom’s imagery would seem to be far from the aesthetics of a teenage lesbian she saw no boundary between the world he presented and her own. “I thought it was so pretty, for me it was beautiful, I was attracted to how the men present themselves more than the specifics of the sex acts, which I also enjoyed because they are so satirical. Through his work I saw a whole universe, and this helped me to shape my own freedom.” Even though the characters’ body types in Tom’s drawings are depicted as hyper-masculine, the facial expressions and reactions the men have to each other have no restriction. Silvia explains:“Tom’s men are flirtatious, coy, humble, happy, embarrassed, confrontational, shy, courageous, joyous, proud, aggressive, and affectionate. They move between hard and soft aspects of personality that are typically prescribed to one gender or the other."

The impact Tom had on Silvia’s life choices and artistic practice are profound. In Tom she saw aspects of herself, an alienated artist who used their work to create an acceptable place in the world for an unacceptable identity. This empowered her to never conform her own identity to be accepted by any group. Artistically, she also followed in Tom’s footsteps. She chose the pencil as her tool of expression, and like him her process involved obsessively cataloging magazine clippings, collaging them and re-rendering them. There are also parallels to her approach to distribution; Tom reached his audience through magazines and books, contributing to the erotic men’s fitness magazine Physique Pictorial and distributing his own comic book Kake. Silvia contributes drawings to all of her favorite culture magazines including V Magazine, V Man, Candy, Dazed and Confused, Fanzine 137 and EY! Electric Youth and also reaches her audience with books: Silvia Prada Art Book (2006) and New Modern Hair, A Styling Chart (2012).

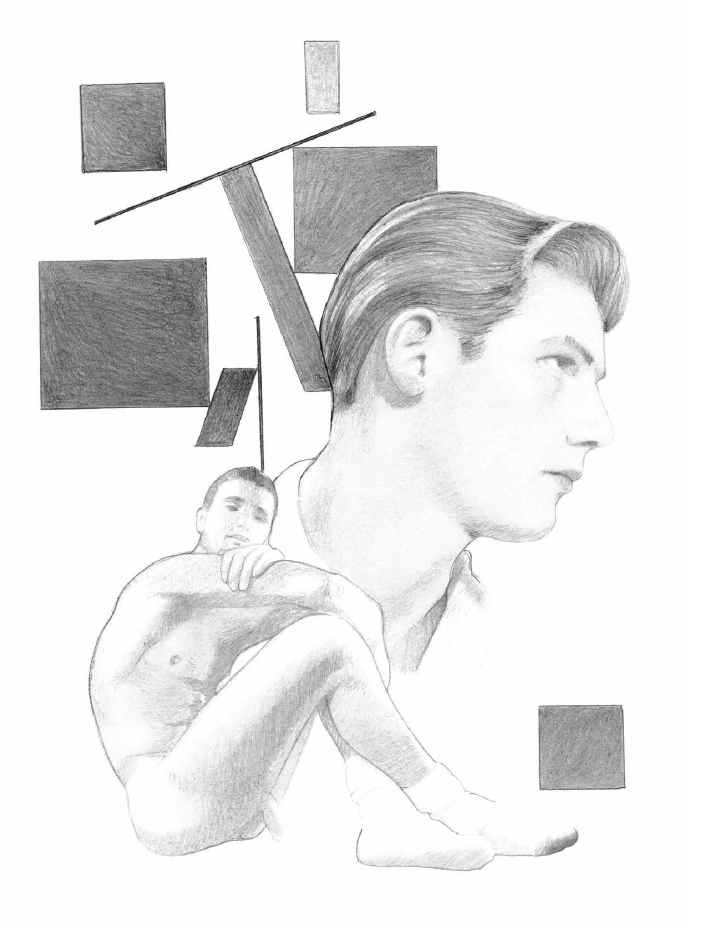

But while there are strong parallels to Tom’s technique, medium and exploration of identity, their artistic strategies differ widely. Silvia’s work isolates transformative moments in pop culture, re-creating mass images with her own hand to make them personal and intimate. “Pop culture has great importance in the moment it’s released, it has the power to change people’s lives by giving them a taste of new possibilities, but it’s fleeting. It only hits the generation whose time it was made for.” Silvia’s work recombines and rearranges pop fragments giving them the reverence and meditative space that art allows its subjects. She gives permanence to the ephemeral, shining a fresh spotlight on important forgotten moments. “I admire people that pay respect to forgotten icons, it’s important not to forget, so you must insist on that over and over and over again.” Prada only draws figures that give her joy: a masked Madonna grabbing her crotch (from her 1992 book Sex), the young cast of male actors from The Outsiders, a reclining Richard Gere via American Gigolo. She often combines these icons with geometric abstraction. Using shapes that reference the movement in 1980s graphic design that repurposed the work of artists like Kandinsky or Mondrian and brought them into the pop-space of shopping malls and music videos.

With the inclusion of these forms Silvia collapses cultural hierarchies while she emboldens her own aesthetic world. The overall approach is disarmingly light hearted: the work has the feeling it was made by a gay teenage fanboy that is the star of his high school art class, but under this playful surface is the serious issue of identity politics and an intent to pay respect to the fragments of culture that formed Silvia and gave her agency.

Working with the Tom of Finland Foundation, Silvia was given access to Tom’s archive of source material, a combination of photo’s from Physique Pictorial photoshoots, porn magazines, and mass media. Looking through the thousands of images he amassed she chose pictures of the men that spoke to her own sense of beauty, sexuality, and empowerment. “There is something political in this book,” Silvia states. She feels that the subversive gay culture that nurtured her as a teenager has currently lost its edge, and become “straight-washed” as it merged into and was celebrated by heterosexual society. Here, she again uses drawing to call attention to an important past moment when gay identities were first developing. She doesn’t revisit the hard-core aspects of Tom’s imagery because “there is nothing to add to his mastery,” she explains, “and even though I can do it, I don’t enjoy as much to draw penises.” Instead this is an exploration of types, styles, expression and identities.Silvia meditates on and brings attention to the characters we have lost in the march towards acceptance. The models showcased and redrawn here examine the outlaw rebel spirit and celebrate the balanced energy that is created by men that are at once the object and objectifier. The porn models in Tom’s archive are radical sexual renegades; despite all of society’s backlash, these men acted as honest witnesses to their desires, allowing their faces and bodies to be photographed in a time where that could have cost them their jobs, their families and their place in society. “I connect with their defiant attitudes. For me to be gay is not just a sexual option, it’s an energy. It’s a shared culture.”