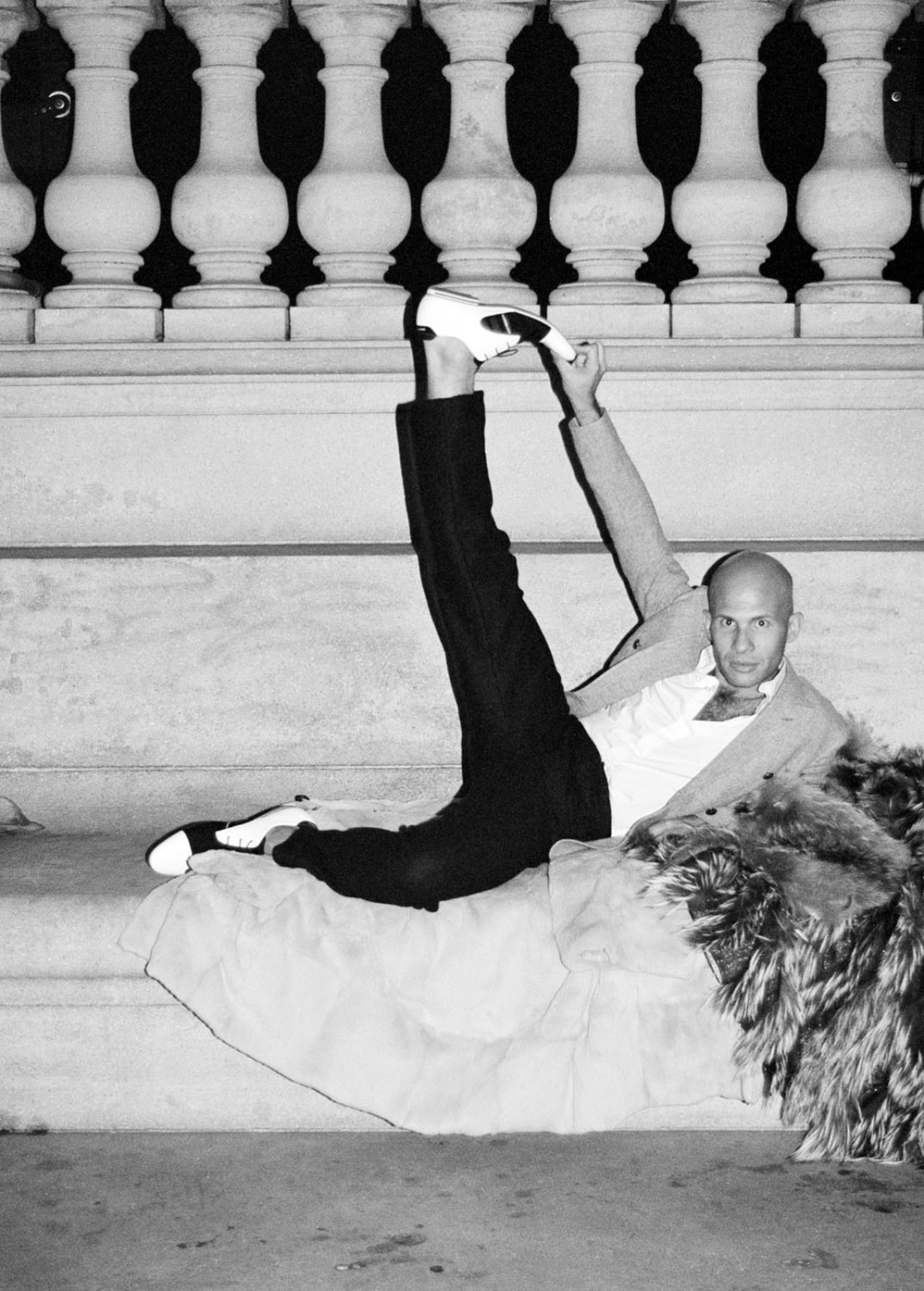

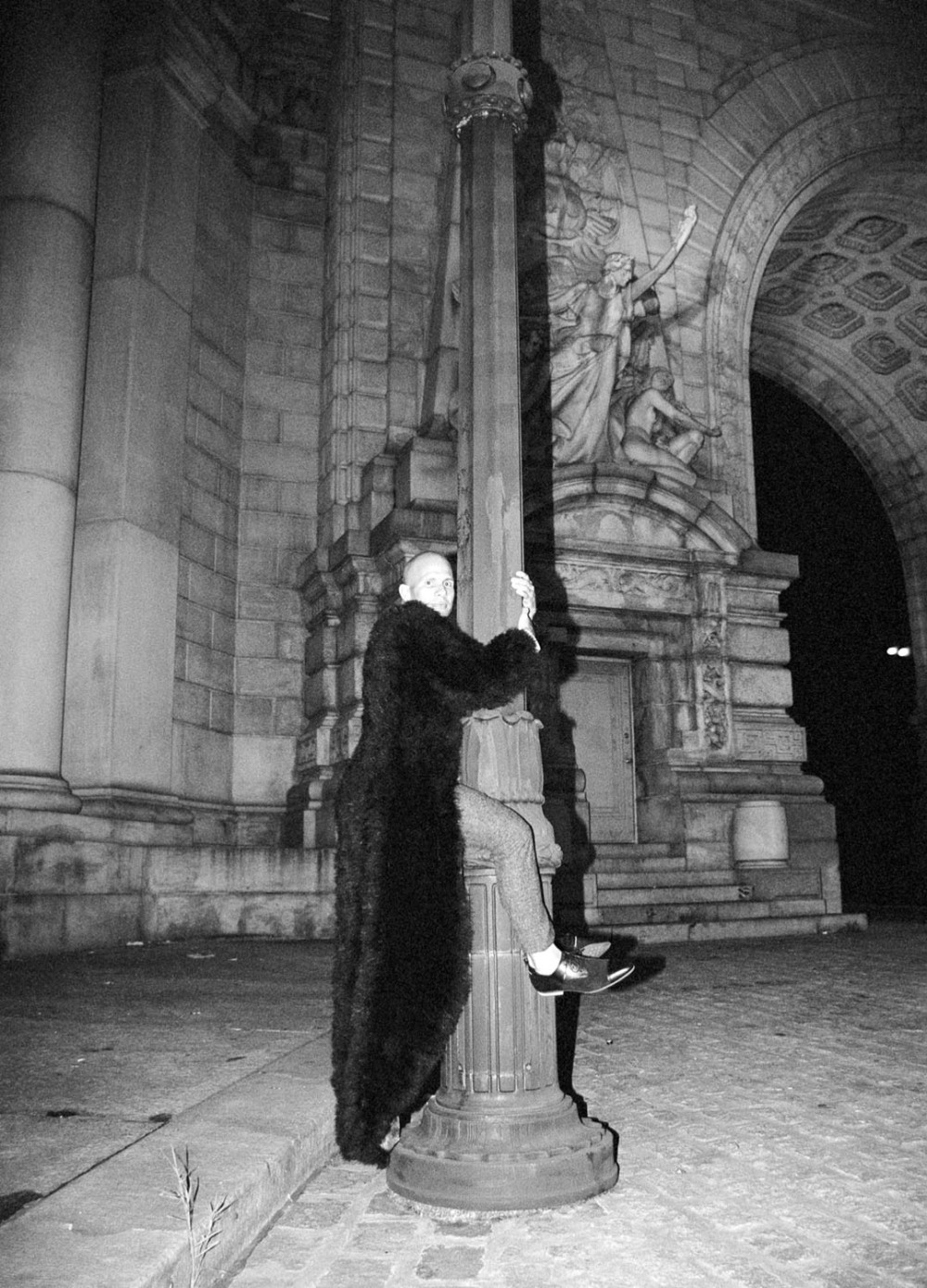

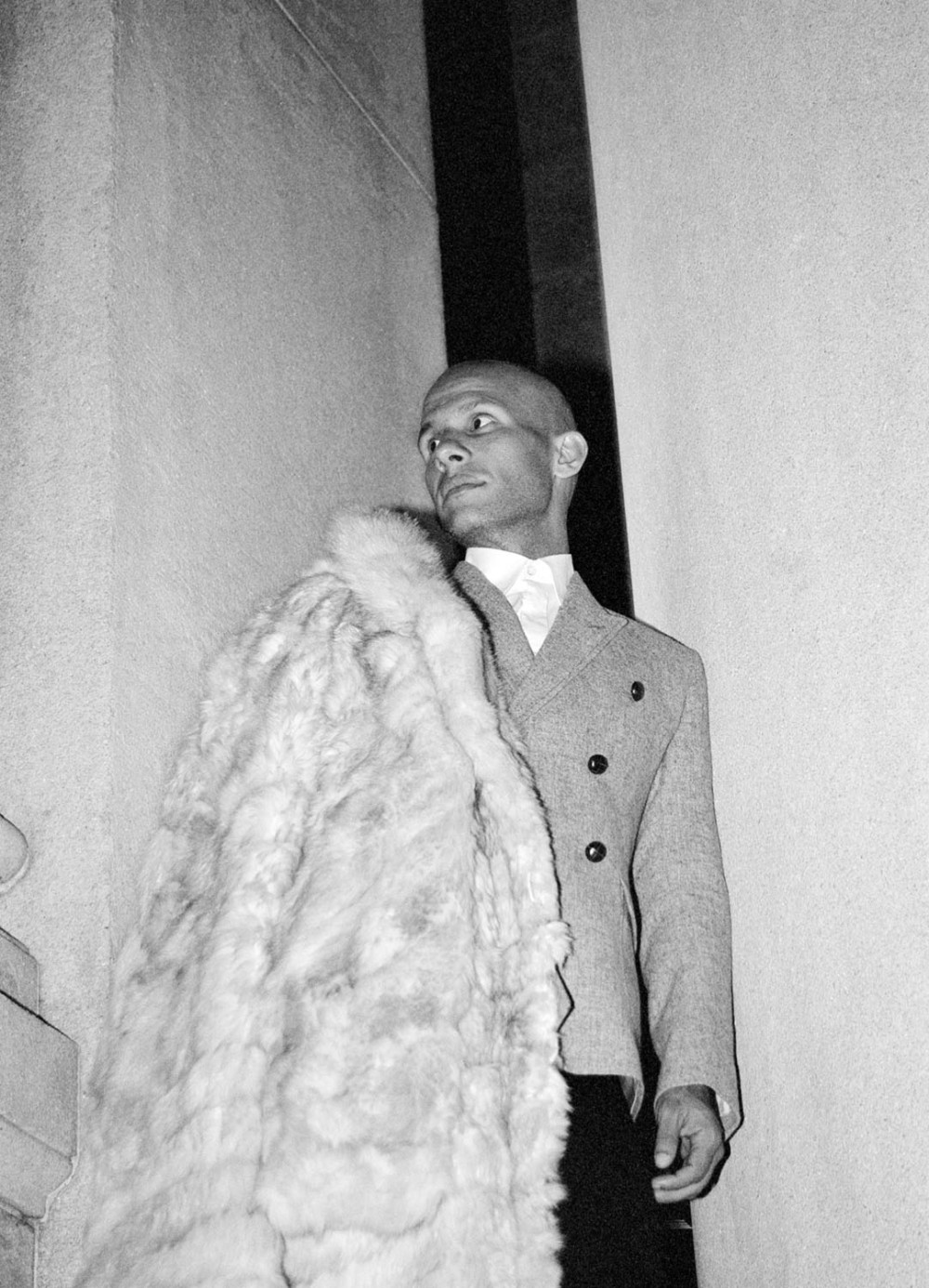

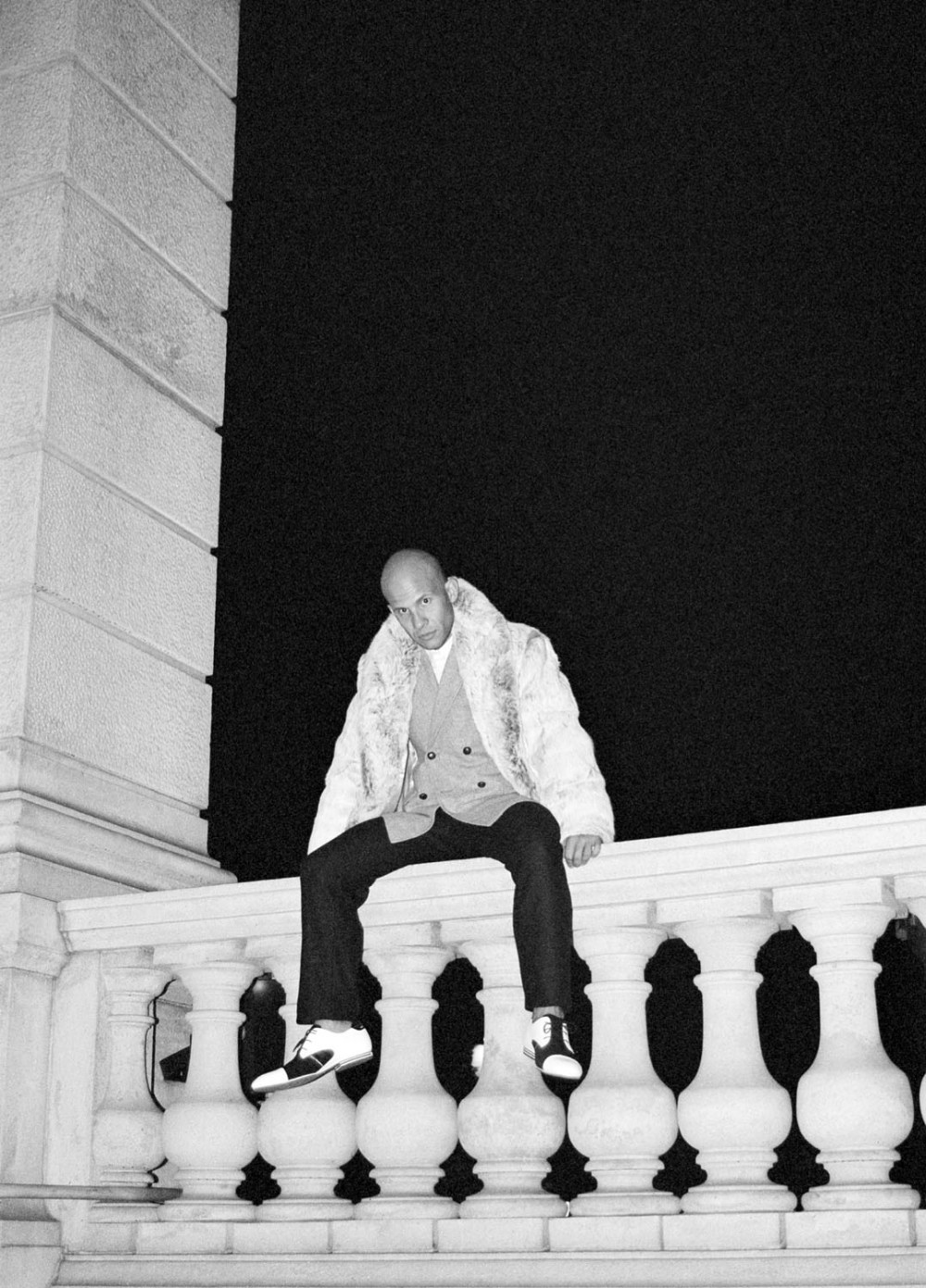

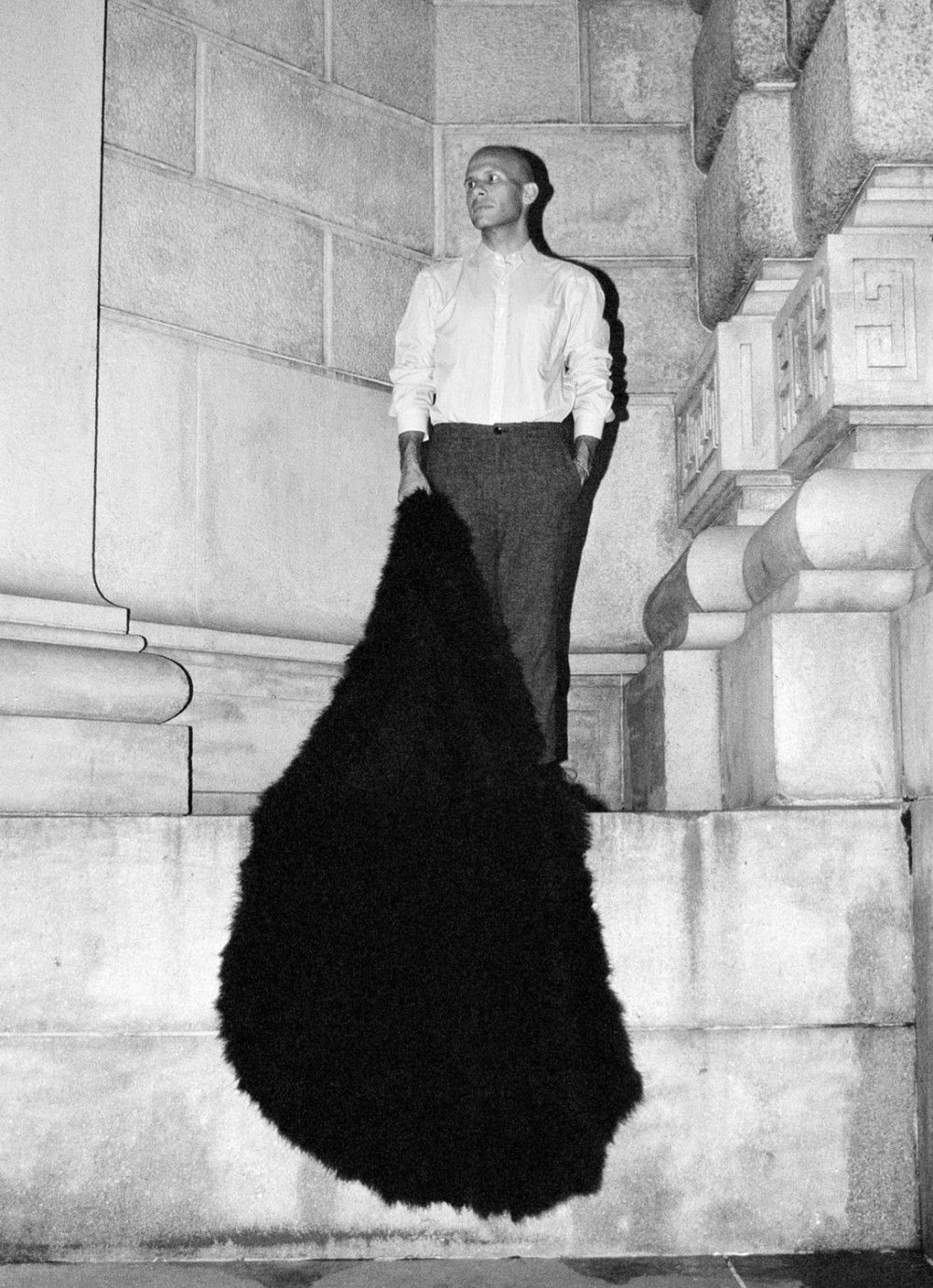

RAFAEL DE CÁRDENAS

The day I meet Rafael De Cárdenas, the 36-year-old New York-born architect and interior designer was still in awe from a Beyoncé concert the night before. “It’s all about her mannerisms,” he exclaims, flicking an imaginary mane of hair from side to side. We’re seated in a booth at Niko, a tiny Japanese restaurant on Mercer street in Soho that Cárdenas designed. In many ways Niko is exemplary of his approach — a mix of classic upscale-eatery elements: bold colors, dynamic patterns, low-brow materials, and specially commissioned artists’ pieces (in this case by Jim Drain). Since founding his firm Architecture at Large in 2006, De Cárdenas has made a name for himself with a slew of eye-popping, media-genic projects, including retail, furniture design, art installations, and residential commissions (for actress Parker Posey and model Jessica Stam, among others). De Cárdenas never strives to reinvent the wheel, but rather to convey, and perfect, a certain mood or moment. But behind his often surface-heavy designs is a sophisticated thought process fueled by a set of references that owe just as much to his background as a menswear designer for Calvin Klein as to his work for architect Greg Lynn and scholar and theorist Sylvia Lavin. In conversation, de cárdenas is refreshingly unpretentious — what matters to him most is creating architecture and design that is as contemporary and relevant as a hit pop song.

Explain to me again, why did you think Beyoncé was so mind-blowing?

Because she sings, moves, and performs like she is Beyoncé — no one else can do that. her movements, her choreography, they’re hers. And the way the music relates to it all, it becomes a motif that runs throughout and becomes a language. she hasn’t invented anything new, but she’s perfected certain mannerisms and completely made them her own. Few people are able to hone their performance in such a specific way and captivate everyone — and that’s exactly what she does!

Let’s talk about your own performance. how did you transition from fashion designer to architect? the more typical story would be the other way round...

I first studied at Rhode Island School of Design and was recruited directly out of school to be a menswear designer at Calvin Klein. But I always had an interest in architecture — I don’t know why. so I thought I would study architecture and then go back into fashion, but as a show producer. At the time I was really into Alexandre de Betak, and I thought that that’s what I would do, too. But then, when I started architecture grad school at Columbia, I actually really hated it. So after my first year, I transferred from Columbia to UCLA.

What did you hate?

This was the mid 90s and architecture was going through that whole conceptual “We don’t make anything, we just talk about shit” phase, especially at columbia. I just wasn’t into the whole paper architecture thing. I believe that as an architect, or a fashion designer, or a writer, you need to make the thing you practice. You can’t just talk about making it. there’s a weird thing in architecture — that somehow complexity is celebrated for its own sake. I don’t care about that. I may not be the most talented or the smartest architect out there, but I’m enough of both to do architecture the way that I want to do it. And I’m always pushing it further in the direction I want to go. But I didn’t learn to think this way until I went to UCLA and started working for Greg Lynn.

Were you his star student?

I wouldn’t say star, but I was definitely one of his favorites. more importantly, I was one of Sylvia Lavin’s favorites, his wife and the head of UCLA’s architecture and design program at the time. I think that’s how I got into Greg’s good graces.

Do you consider them your architectural mentors?

Yes, especially Sylvia. She is awesome and I owe her a lot. When she was my thesis advisor, I remember she once asked me to describe two projects, one by Steven Holl and the other by David Chipperfield. I used the word “elegant” to describe both and Sylvia scolded me, explaining that the word “elegant” means so little: it only means elegant, and elegant is something that you know only when you see it. she said the way I described those projects, they sounded like one and the same. I began fumbling for the right words and she told me, “the words exist — you just need to sharpen your knives.”

So after you graduated from UCLA you went to work for Greg lynn, helping him teach (at the Universität für angewandte Kunst) in Vienna, and working on the World trade center competition back in 2003.

Yes. the time I worked on the World trade center competition was probably one of the highlights of my life. Greg had joined forces with reiser + Umemoto, Foreign office Architects, and Unstudio, and we all entered as one team under the name United Architects.

That’s a lot of ego on one project! How did they all collaborate?

It actually fragmented into what people were naturally good at. the towers were designed by everyone, but, for example, Unstudio figured out the whole transportation hub — the subways, the freeways, vertical circulation, etc. — the overall logistics were largely figured out by Foreign office Architects, Greg lynn’s team was responsible for 3d-modeling software, and so on. so the division of labor happened organically.

You were the new school team?

Yeah. Herbert Muschamp from the New York Times even called us the “dream team.” he championed us in a big way and he would come once a week so we could show him our progress. I remember his references were always cultural. one day we were talking about the New York Times magazine’s competition for a time capsule, and he said that calatrava’s submission, in elevation, looked like may West’s lips, but then in profile it had this big sharp peak that would cut you if you actually tried it to kiss it — he called it a deadly kiss. I loved that reference!

The work you’re doing today is very different from Greg Lynn’s. how did your time with him most influence you?

I learned a certain methodology from Greg. But Greg’s studio was run very differently from the way I run my practice now. In a weird way, it was more hierarchical. It was Greg’s singular vision, and I don’t know that I’m strict like that. First of all, I don’t champion my own style, because style by nature is easily exhausted — it has a lifespan. so I try to move beyond it and suggest moods and atmospheric effects. In a way, I learned mor eabout running my business from Calvin Klein’s studio, at least from an organizational standpoint. the idea of being commercially successful while running a design practice that’s culturally relevant may sometimes seem incongruous. But calvin Klein, at the time I worked there, made a strong contribution to the world of design while also making a great profit — so I learned that those two can be harmonious.

It’s funny that you learned to run your studio from a fashion designer, because I would have thought the goals and pace were too different to be applicable.

I don’t think that different sets of rules necessarily apply to fashion and architecture. contemporaneity is the same, whether in fashion, or writing, or anything else; there’s a way to be contemporary and you have to know what that is. You have to be very familiar with the zeitgeist, have your ear to the pavement, and know what is going on, in order to diagnose it immediately and create the contemporary.

But the time frame in each field has a big impact. Fashion turns out two or more collections a year while buildings can take forever to be completed.

Well, one definition of architecture is the construction of a freestanding building. Alternatively, you can claim many types of projects that work architecturally, which is what I do. Architectural work can be made at many different scales — I’ve done full projects out of tape or saran wrap! many people probably wouldn’t consider that architecture, but I don’t really care what they think. I consider it architecture and I claim it for architecture, whether architecture will have it or not. Because the discourse of architecture, to me, is not very culturally relevant. It’s far too tied to academia, and academia is out of step with the contemporary.

The first time I heard mention of you was in relation to the Anything clothing store on Hester Street on the Lower East Side. Was that your first project under your own name?

Yes, although at the time I was still working full-time for (film-production company) Imaginary Forces. But I was working on experience-design projects — which were very costly to produce — and they stopped happening because of the economic downturn. so I started working on my own projects more and more. Parker Posey’s apartment and anYthing were the first.

Anything was also the beginning of a long collaboration with Aaron Bondaroff, who has since founded the gallery, art publishing house, and international pop-up shop ohWoW whose spaces you also designed. Would you say that your work for Aaron is the best representation of your own style?

I don’t think I have a signature style. It’s just that all the projects I’ve created for Aaron are almost all one brand, so it’s good for them to be branded. I like commerce — I don’t think it’s a bad word. retail space has to be commercially viable. But I also do a lot of residential projects which, by nature, are very different. I play out a lot of my different interests in all of my work. I think that part of being a designer is designing something that is appropriate to its use, and to the specific brand.

But then your residential work is very different. Many of the projects, like the apartment you did for Jessica Stam, are a very brightly colored take on 1930s and 40s Hollywood glamour.

You’re right, a lot of my residential projects have this kind of 1930s, Billy Haines, Hollywood-boudoir, L.A.-film-noir glamour gone sour. that’s appealing to me in a huge way, like a sickly sweet femininity that’s cut by something catastrophical. I like residential interiors that do that.

There is a lot of drama and bold color, but there’s also a lot of comfort.

But there’s also discomfort! It can be uncomfortable when someone diagnoses who you are. I don’t always necessarily give my clients what they ask for...

Are you talking about playing psychologist with objects?

Well, to a degree, objects are all about psychology. they mean something, and their organization and reorganization can mean different things, sort of the way words have different meanings in different orders. of course ultimately I want my clients to like my project, and they usually do. But 100% happiness with my project does not equal happiness — you could have the most bangin’ interior in the world and still have a shitty life, and vice versa. so you can’t give it that much importance either.

One thing almost all of your projects have in common — whether they’re residential, retail, or otherwise — is the use of electric color and decorative patterns, two things most architects are afraid of.

Architecture with a capital A, the way that we’ve inherited it from modernism, is a very macho practice and it has completely divorced itself from interior design and decoration. most architects are basically afraid to put on some lipstick and a little eyeliner — they’re afraid to be caught in drag! But I think that architecture is already decoration: we plasticized the way we were supposed to live so long ago, and buildings per se are totally artificial. so I don’t understand why there is so much fear attached to further micro-embellishment. the nice thing about interior decoration is that it’s allowed to not be macho. It’s not scrutinized with the same intensity. Yes, decoration suggests things like status and social hierarchy, but in architecture history, long before the arrival of modernism, decoration also served very simple purposes. For example, a baseboard simply hides the imperfection of how a wall meets the floor. those are useful devices, and they can take any form you want. so I decorate everything as much as I want to because decoration is another layer of meaning that you can add to a project. Architecture may be macho, but I’m not!

Another decidedly un-macho trademark of yours is the pop-up shop, of which you have done quite a few. What do you think of this phenomenon?

It has market appeal, and it’s also a useful tool for the kind of end-of-the-world economy we’re living in right now. there’s a lot of uncertainty and it’s hard to make a ten- year financial plan, because who the fuck knows what’s gonna happen? so I think the pop-up store phenomenon is a product of that sentiment. It also seems a very appropriate concept for a generation that is so steeped in the ephemera of media and social networking. the pop-up store is a physical manifestation of the tweet — they have a kind of relationship. But I think the pop-up store, at least in title, is already exhausted.

In a way, you’ve used the current economy to your advantage though, making a name for yourself with mostly small-scale dynamic projects.

I’ve only ever worked in this economy, so it’s not like I had some boom-time economy and then I got hit with this — it’s all I know! I’m varied because of my experiences in fashion, and because I have a sort of innate commercialism — which I don’t know where I get, maybe it’s just being Jewish — and somehow I’m able to make things work. But I’m by no means established — I feel very precarious!

You may feel precarious, but you were recently able to launch an entire 25-piece furniture collection at Johnson trading Gallery. how did that come about?

I knew Paul Johnson before because I’d bought furniture from him for clients for a while. One day he asked me if I designed furniture myself, which I didn’t really. And then he asked if I was interested in making some. It was very different from anything I’d ever done, so I approached it the best way I knew how, purposefully referencing the furniture design of other architects — Bruce Goff and Frank Lloyd Wright, specifically.

Were you nervous having a big show like that? It got a lot of media attention.

I’m still nervous about it! I never set out to produce a show that people would react to so strongly. But I’ve also heard some rumbling within the design community that’s gotten back to me...

Well, I think it’s obvious that you have different interests to most furniture designers. At Johnson trading Gallery especially, you see impeccably crafted high-concept design, made with incredible materials. Your work, by comparison, seemed far more focused on the visual impact. Maybe this sounds horrible, but your show was almost like a Lady Gaga moment in furniture...

I don’t have a problem with a Lady Gaga moment in furniture! I actually prefer design choices that date objects and fingerprint them to a specific time and which suggest the greater cultural context. For example, I’m far more interested in the avocado-green stove at case study house #21 than some beige one that has never been contemporary and always classic. Being contemporary is more interesting to me than being tasteful.

Does that attitude better prepare you for criticism, or can it still make you uncomfortable?

I don’t think anyone likes criticism. I know I don’t.

Of course. one would always rather have one’s work seduce.

Well, everything in life is seduction. You want everyone to fall in love with you, and to love everything you do. everybody wants that, no?

Hmm... I think most people are motivated more by money than by the desire to be loved.

Monetary gain is part of it, but if my goal were to make lots of money there are far more efficient ways than being an architect. And the very specific thing that I claim as architecture most architects probably would not, and they don’t want me in their club. so I’m actually all about being part of a club that wants you out — that makes me want to be part of it even more!