MONTROSE AVE,

THE SPECTRUM

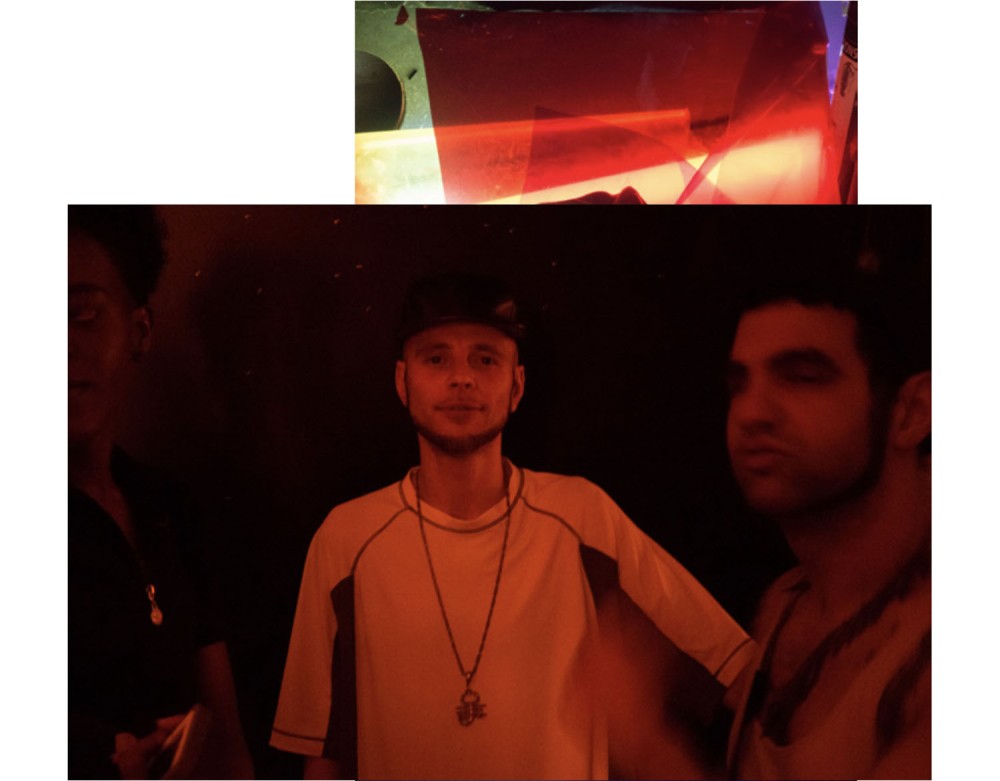

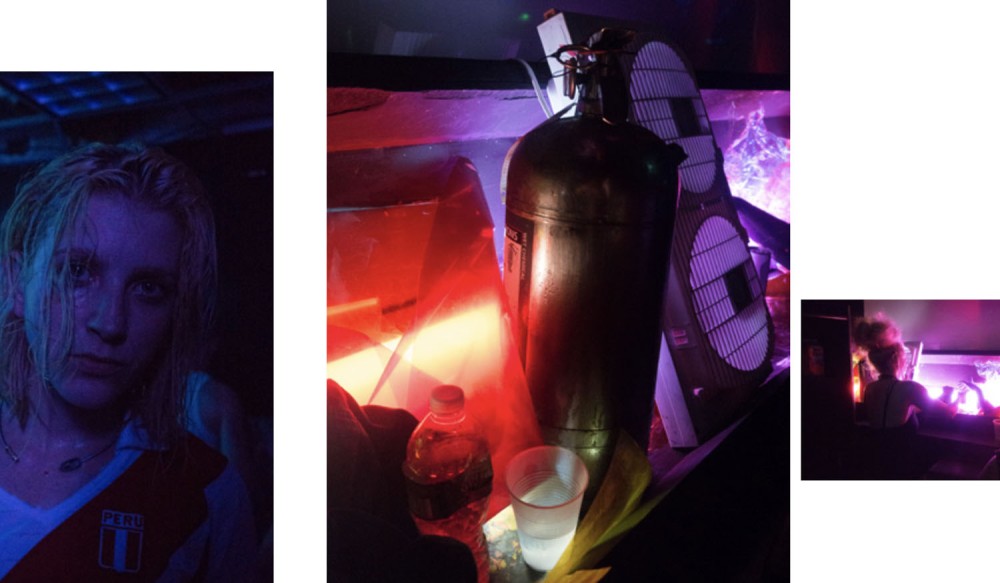

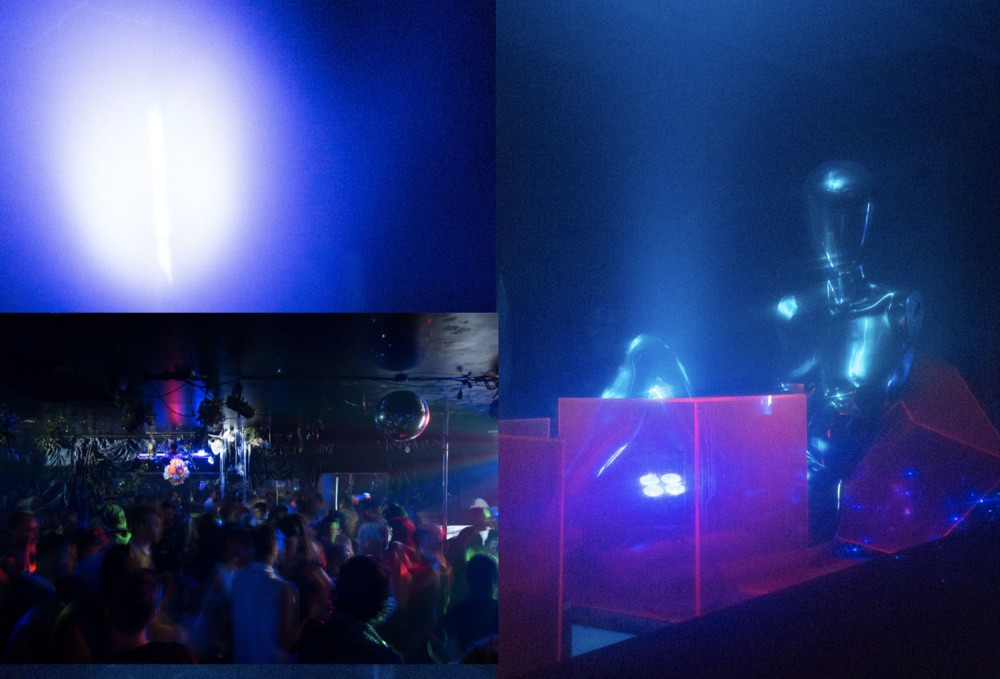

3am in New York City. It’s the middle of a Saturday night that is nowhere close to ending, and the next stop will have to be Montrose Ave, an unassuming street in the Puerto Rican section of Williamsburg. Looking at a group of quiet row houses, you wonder, ‘Is it happening tonight?’ and you try to remember which door will lead you through to the Spectrum. When you choose right, your night begins. A friendly security guard with the silhouette of a scorpion shaved into the hair on the back of his head ushers you off the street into a long peach-coloured hallway. Here, you’re greeted by a message scrawled from floor to ceiling across the wall in purple spray paint. It reads, ‘Thank you for helping us maintain a safe queer community space’. These grateful words gently remind you that what you’re about to experience is not just any night club; the Spectrum is the product of an ethos deeply rooted in queer politics. It tells you, ‘If you’ve found the Spectrum, you’re a part of the Spectrum’. It’s not VIP, doors are open to all, but being here means that you are a member of a self-selecting family made up of disenfranchised members of society: queers, trans, orphans, artists, performers, gypsies, freaks, punks, hedonists, as well as lost boys and girls of every kind. Once through the narrow dark hallway, you come upon an expansive mirrored dance floor. This is what you came for: a sea of sweaty revellers in various states of undress, dancing in a trance, engaged in a celebration of each other’s music and art, minds and bodies. The Spectrum could be described as a nightlife co-op, in which every guest contributes their part in order to make it happen. But sadly, on New Year’s Eve 2015 the Spectrum threw its last party, becoming the latest casualty of New York’s rapid-fire real-estate market. While most people may have thought of it as an after-hours, it was actually a 24/7 centre of queer action. Its structure was unique, the decadence of the night was built upon the creative productivity that happened in the space during the day. In 2011, the performance artist Gage of the Boone found the live/work location and thought it would be an ideal rehearsal venue for himself and his friends. It was from this humble idea that the Spectrum was born, and it grew organically into an international cultural hub presenting cutting-edge music and performance art that was a hotbed for emerging talent.

A few days after their last party, I sat down with Gage and two of his closest allies and collaborators, his roommate, artist Raúl de Nieves, and Danny Taylor, AKA A Village Raid, who was the resident DJ and music curator. The three explain how, against all odds, during the most oppressive economic era in New York City’s history they successfully maintained this period-defining illegal nightclub for five fantastic years.

Give me your brief geographic biographies. Where did you meet?

Gage of the Boone: I was born in Colombia and was adopted. I grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts, then went to San Francisco for art school. I went to the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland. I started as a fashion major, but the performance installation, video, and sculpture departments were way better, so I individualised my major and worked on pretty much the stuff that I do now: performance-based installation. That’s where I met Raúl, when we were 20.

Raúl de Nieves: I was born in Mexico and then moved to California in 1993 with my family. I applied to go to CCA and I got in, but it was too expensive for me. I decided to move to San Francisco and be there for four years and act like I was in school.

Gage: San Francisco itself was a formative school-like experience, in terms of queerness and radical existence. There isn’t much money in the art scene there, so if you were performing, or making music or art, it really was for the love of it.

Raúl: I wanted to be among the freaks, I fantasised about that. That’s where I first started identifying myself as queer; it was this totally different way of thinking for me.

How do you define queer?

Raúl: Especially now, the word embodies so many different people’s perspectives. It’s an individual way of putting yourself in a category, but it’s open to every difference. Every person is their own type of queer. You paint your own picture. The more you get to know yourself, the more you can truly identify with that concept. Boundaries are not even important anymore—sexuality or even gender become secondary.

What did that mean for you in terms of style? How did you dress during that time?

Gage:I wore a lot of ruffles. We both had short, curly hair that was very light. We looked like angels. San Francisco is so nostalgic: you can see every time period walking around. It’s acceptable to pull from every era. There are rockabilly girls and ‘20s people. Our look was very ‘70s, when psychedelic went into a whole other dimension, and then it was mixed with— Raúl: Heavy-metal influences, but very California, very tripped out. Counterculture is just more an accepted thing there. In New York you’re more aware that there are many worlds. Here it might be about presenting yourself in a way where you can actually have a conversation with anyone, rather than excluding yourself.

Gage: The fashion industry here also affects how people dress more than it does in San Francisco.

Raúl: In New York, nightlife is an opportunity to dress up. In San Francisco, it’s 24/7. There were phases in my life where I would just wear heels and miniskirts all the time—but I didn’t consider myself trans, I was more gender queer.

Why did you move to New York?

Raúl: San Francisco is so small. We did everything there multiple times. I moved here in 2007, maybe because New York’s so romantic.

Was it always your plan to open a space?

I was living at my friend’s house, so I was looking at craigslist all the time for my own apartment or a commercial property, because you can get more space for less money. I wanted a place to live, make art, and rehearse. I was trying to figure out how I could live in an alternative way. I had always wanted to have a queer community space. That’s how I found the Spectrum. Ironically, I had no money.

A club was never your intention?

Gage: No, it was all about making art. But I was working in nightlife at that time, and I had already thrown some parties. So I was like, ‘I know how to make some fast money to pay the rent’.

What was the history of the space?

Gage: When the landlord first showed us the space it was really creepy. They hadn’t cleaned it up since the last thing. The energy in there was dark. The room in the front used to be a Puerto Rican sports bar; the big space in the back had initially been an aerobics studio, and that’s why they’d put up the mirrors. During the sports-bar phase the aerobics studio became a secret backroom with a stripper pole. My landlord’s friend told me, ‘This place was really wild, man’.

You kept up the tradition.

Raúl: Maybe in a healthier way, question mark?

Why did you name it Spectrum?

Gage: In New York at that time parties felt segregated; they were either straight or gay. Even gay and lesbian, or trans and gay, didn’t mix that much. We wanted a name that let people know it was a space for everyone, the entire spectrum.

You actually lived in the party space for the first year, right? Did it have a shower?

Gage: It did. There was a shower in there, but it was such a problem. Everyone would pee in it, and it didn’t drain the right way. My friend Dake Gonzalez made an executive decision: ‘We’re putting urinals in right now’. It saved our lives, because having to mop up everyone’s stale piss was the worst.

I always thought Spectrum was created to be an after-hours?

Gage: That was never my focus. It’s such a risk and honestly just not a good business plan. Although it was always a struggle to get people there before 2am.

Anyone that went is amazed that you managed to keep an illegal underground club open for five years. What was your secret?

Gage: There are certain things we probably shouldn’t talk about.

C’mon, it’s over.

Gage: The Spectrum was a success because it was a community space that was utilised for art. We had hundreds of nights of performance art, concerts, and poetry readings. And then during the daytime it was a very active space where people used to make music videos or do photoshoots or rehearse or host workshops.

Raúl: Some neighbours complained at the beginning, before they were able to understand what we were doing. But the longer we were there, they realised that it wasn’t a club. It wasn’t open every weekend; we would only throw parties once or twice a month. It ended up supporting a lot of local businesses, and so the community ended up supporting us.

And the police left you alone?

Gage: The first time the police came it was a pearlescent-themed party; the whole space was shrouded in shiny white fabric. I was wearing some crazy outfit looking like a pearl. The aesthetics was too much for them. They just said, ‘Oh god, not another art show’. When they realised it was a bunch of art kids having fun and enjoying their lives, they were like, ‘This is a waste of our time, we could be preventing someone from getting murdered right now’.

Raúl: Once during after-after-hours, at like eight in the morning, I was on mushrooms having sex in my bedroom and someone was knocking at the front door. I thought Gage had locked himself out. I was completely naked; I planned to open the door quickly and run back into my room. When I opened it the police shouted, ‘Put your hands up. Don’t move!’ And I was like, ‘I’m naked’. I don’t remember how that ended.

Gage: Someone told them a stab victim was dragged into our building. They didn’t realise it was a private home. They were really apologetic.

I get a sense you had a lot of visitors. Besides you two, how many other people lived here?

Gage: That was the cool thing about Spectrum. A lot of the kids passing through were transient, and it was good that New York had somewhere they could stay. The space was there for them. It felt like it was already theirs.

How did strangers know you were open to that?

Gage: We were part of this queer network of international travellers. Before I moved to New York I was a traveller, so I was connected to a lot of similar places. Once Spectrum started I still travelled a little bit, and I would tell people about it, and they would visit when they came to New York. [DJ Danny Taylor enters the room.] That was what happened with Danny and Kerrie Ann Bearcat. Then all their friends from England started coming, as well. It was very interconnected—one little queer hub with roots in many different cities, which was great.

Danny, how did you meet Gage?

Danny Taylor: I saw him on the streets of Whitechapel; he was wearing a clear plastic outfit. I was like, ‘Who, what is this creature?’ Because there was no one in London like that.

What was your first impression of the Spectrum?

Danny: It was very refreshing for me because it was a new arts community and everyone was young, whereas London always felt a bit stuffy. There are lots of people from the ‘80s and ‘90s, and it’s just so heavy; you have to go through all these hierarchies before you can get anywhere. New York blows up and then dies. It’s constantly generating the new.

Raúl: There were a lot of different phases in the living situation: Pozsi Kolor lived in my room for a long time before me. And then Devon Rainey, who performed on New Year’s, also lived there. In the meantime, there are a lot of people like Granny and Mona and our straight brother Joe Heffernan who also used to live here.

Was it difficult to keep up with so many different people and events?

Gage: I definitely have the right type of personality, fortunately or unfortunately. Although I had a few breaking points that were serious. When I was living downstairs it became a level of dirtiness that was horrible. I realised I couldn’t live in the club space anymore, and, organically, that’s when the apartment upstairs opened up.

Raúl: I remember that strangers would always slip off the dance floor and pass out in Gage’s bed.

Why did you have to leave the space? Is the building being torn down to make way for luxury condos?

Raúl: Just like everything.

Gage: No, we didn’t have a lease, and the building was sold in bankruptcy court. So, technically, the Spectrum was a government institution. New York City owned it for a little while.

Without any funding. I’m impressed that living in a quasi-public nightlife space your lives didn’t descend into darkness and addiction.

Raúl: That’s questionable. I think it’s true. Spectrum was hedonistic, but for the whole five years the feeling of the parties remained friendly and joyful.

Gage: At most parties in New York, even if you’re a VIP at whatever club, there are always so many rules, and you feel that people are watching you. Spectrum was a breath of fresh air because as long as you respected the other guests, you could get away with anything. People realised that was something they wanted to help maintain. Also, because it was a self-selecting place, people felt like they were part of it in a way that you don’t at most nightlife venues. And because it was in a home.

Raúl: And because it came from a close-knit group of friends and a community that grew and grew and grew.

Gage: In New York, nightlife is a big industry. Most parties are thrown to be photographed. It’s become an illusion of funness. You see the pictures online, and the photos make you think it was the best party ever with the best music and the most beautiful people. When in reality that party wasn’t great. Sometimes you would have fun, but those experiences don’t feel organic. From the start we decided that Spectrum was not going to allow photographers, ever. Without the fear of documentation, people felt much more comfortable about letting go. There were a lot of up-and-coming celebrities, or even real celebrities, that came, and they never got a camera flashed in their face.

Raúl: That created a whole different vibe of positive celebration.

Gage: Also, I wanted it to be a space where people could actually talk to each other and have moments of connection. That became successful when we opened the second room. It was almost like an old-school throwback to have a chill room. Clubs now don’t do it so much, so it was great that people were actually able to communicate and be somewhat productive.

Raúl: It wasn’t even really about Instagram either. People came dressed up, but maybe all that photo PR stuff was taken care of at the parties they went to before they came to Spectrum.

Danny: That environment forced people to let go no matter what they were wearing, because once inside your look just didn’t last long; you would have to take it all off. I saw some of the most precious people strip down and just get on with it. People’s façades had a way of dissolving inside the Spectrum.

Gage: Lots of drag queens would come from Susanne Bartsch’s events in full looks, but it was always more glamazon drag.

Looking beautiful in a conventional way?

Gage: Literally looking like a million dollars. I love that kind of thing. I like doing that sometimes, but when I started the Spectrum I wanted a place for looks that were more dirty, gritty, and crazy, if you know what I mean.

Raúl: Less conventional and a little bit more thought provoking, more creature-ish.

Gage: Also, these specific years in New York for our community were really intense. When you think of everyone that has been a part of the Spectrum and what they have actually accomplished—there are lots of people who were just starting to figure things out for themselves five years ago, and now they are being shown at MoMA or touring around the world. A lot has happened in a relatively short period of time.

I’d never thought about that, but it’s true a lot of people got major recognition. Telfar, DIS, Hood by Air, Gypsy Sport.

Raúl: Marie Karlberg, Stewart Uoo, Jacolby Satterwhite, Stefan Kalmár.

Danny Taylor: Also musically: Lafawndah, Total Freedom, Michael Magnan, Arca, the Carry Nation, SADAF. And queer rap, that’s definitely a New York thing: Zebra Katz, Mykki Blanco, Banjee Report, LaFem Ladosha, Le1f.

Gage: Also Juliana Huxtable, Boychild, DeSe, Bailey Stiles. It was important to me that it was a space for gender to be explored, for gender queers to experiment and to let trans babes have a place where they felt safe and loved. We spent a lot of time schooling gay boys on sharing space with female-bodied queers and fem lifestyle of every sort.

Raúl: These people have been in our lives for a long time. It’s awesome to be able to celebrate your friends; they stuck with their beliefs and made it possible. Most of the people I see that are really successful—it’s because they have stuck together and built a community. And it’s not a single person being like, ‘I’m awesome, I’m Picasso’. It’s like Picasso is now a group of people.

Everyone lifted each other up and gave each other more confidence to go further in whatever it was they were doing.

Gage: I remember moving to New York and people being like, ‘Good luck with having anyone help you out with anything’.

Raúl: ‘You’re going to be in poverty’.

Gage: And then it’s been completely the opposite because the community is really looking out for one another. It’s not a small thing; it extends to some people that you didn’t know were a part of it. Right now, they’re helping you. I’m so thankful that we can experience that in such a way, in such a weird time.

So what will New York’s young artists do with themselves after 2am? Is the next incarnation in the works?

Gage: We’re doing Dreamhouse things right now, while we figure out if we’re going to find another Spectrum space.

Dreamhouse is your production company?

Gage: Yes, it’s basically ‘Spectrum presents’, but we don’t use the name because we don’t want it to blow itself up too much.

Thanks for creating such a special place. It took rare people to have kept it going for so long against all odds. I see running Spectrum as a political act.

Gage: I would have to remind myself of that a lot. But that’s the thing: it was my radical duty, it was my radical artwork. It was a community fucking space. It was a labour of love.