JONATHAN LYNDON CHASE

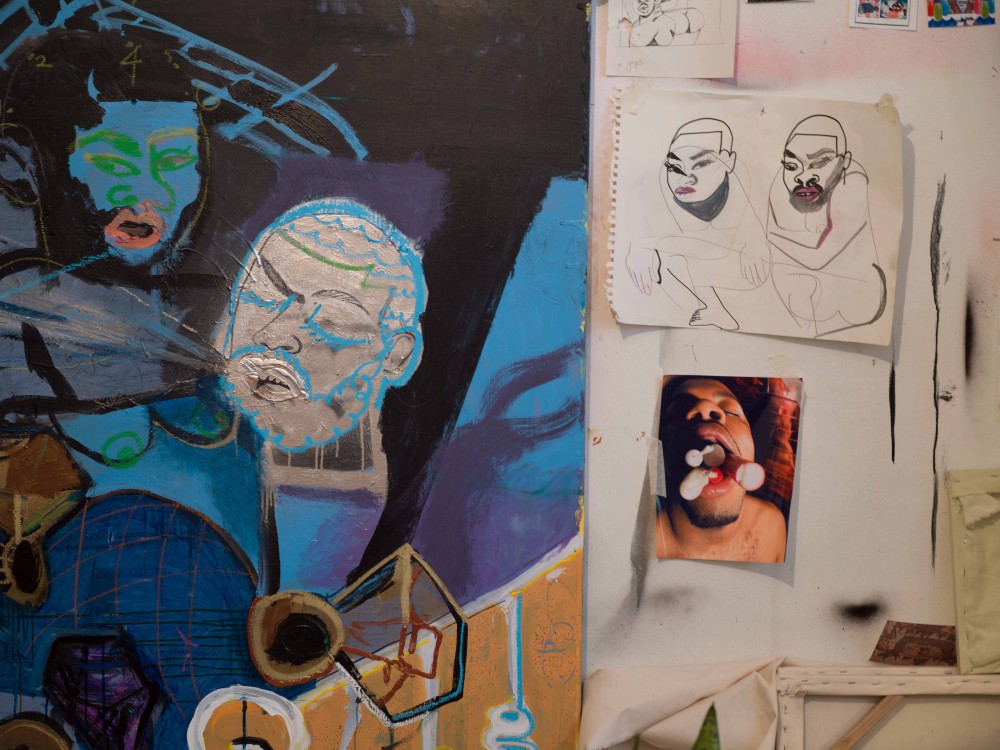

Jonathan Lyndon Chase is at the tail end of a breakthrough year. In 2018, from his home/studio in the Olney section of Philadelphia, the former Baptist-church usher has produced two back-to-back, critically acclaimed, sold-out solo shows: ‘A Quiet Storm’, at New York City’s Company Gallery in March, followed up quickly in June with ‘Sheets’, at LA’s Kohn Gallery. Jonathan’s subject matter is the same as many painters throughout history: he depicts his own life and the lives of the people he’s surrounded by. But his endeavour takes on a radical nature and a political power because he’s the first artist who has captured in painting his experience of life as a proud queer, non-binary, black man. With bravado and honesty Jonathan has made bold, large-scale paintings (often using his own bed sheets as a canvas) that expand our clichéd, commoditised, hyper-masculine, pop-culture understanding of the black male body. His images inject new, previously marginalised figures into this dialogue, bodies that don’t conform to standards of beauty or gender: voluptuous men, submissive machos, bodies adorned with the signifiers of street hardness but engaged in tender moments of pleasure and passion. Jonathan’s paintings invite us into the most intimate moments of his life to experience the intertwined dynamics of desire, sexuality, masculinity, race, and love through his eyes.

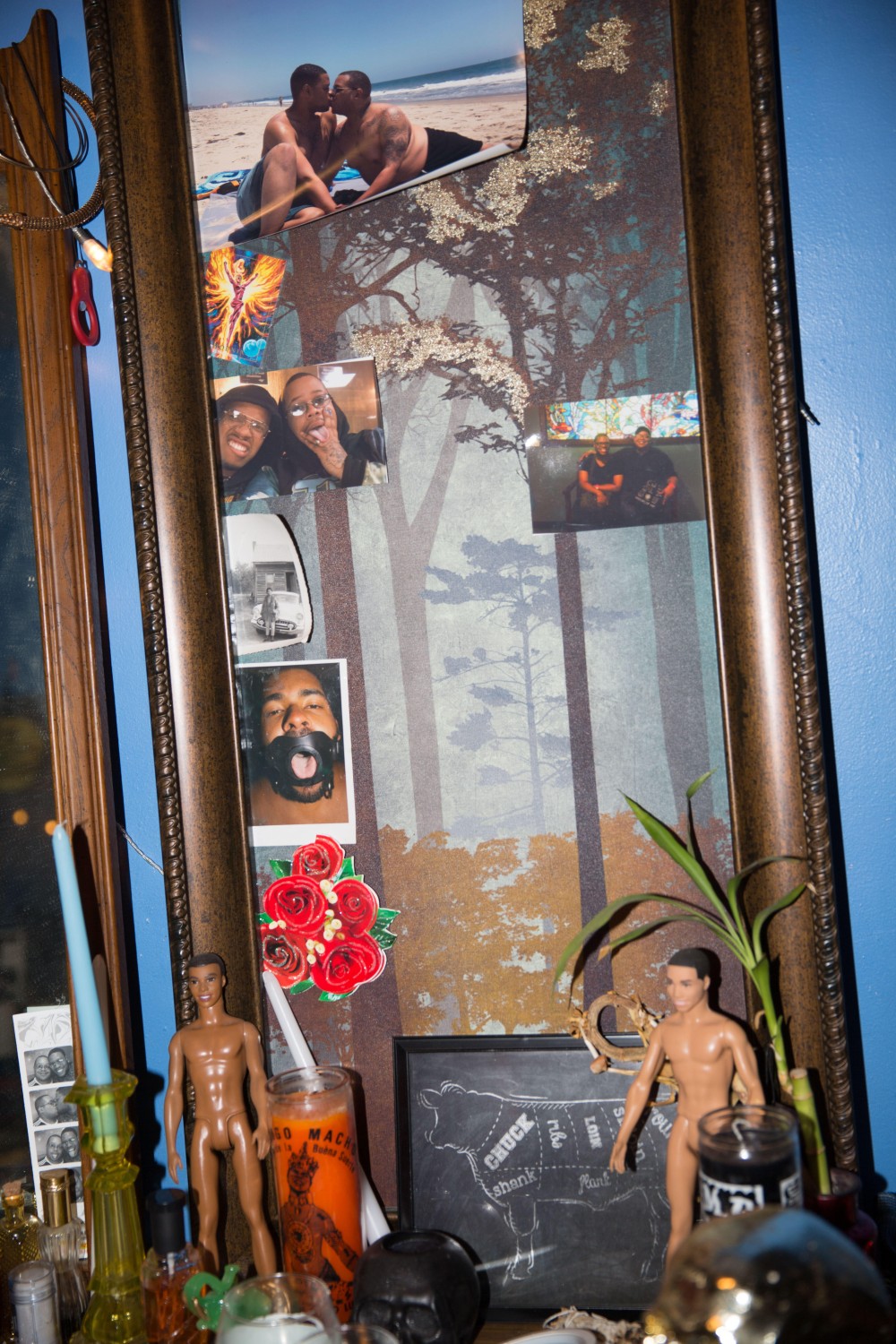

I catch up with him and his husband, Will, in late July at their two-storey row house in North Philadelphia. The lovebirds are attentive, warm hosts. Will offers me a delicious homemade sloppy joe, and they take me on a quick tour of the property. With paintings stuffed in every room of the building it’s easy to understand why these are the final few months before the young couple leave Jonathan’s parents’ home and move into their own place. I’m lucky to catch them in this moment, before the present chapter of their lives closes. Here, in his childhood home, I’m able to get a sense of the support and sacrifice that have led to Jonathan’s much-deserved, newfound success.

I just read the LA Times review of your solo show at Kohn Gallery. The critic, Sharon Mizota, compares your paintings to Egon Schiele and Francis Bacon!

Jonathan: They're two of my favourites. A lot more so Francis Bacon. I really like a lot of artists: Romare Bearden, Barkley Hendricks, Mickalene Thomas, Goya.

I can see those influences, but you apply them to entirely new themes.

Jonathan: I didn't start painting until I got to grad school. That's where I started making large-scale images of unconventional, unapologetic, non-binary, queer black bodies: men that wear makeup, bodies that sag, have titties, that maybe have a small dick or a big asshole.

Were you deliberately addressing the exclusion of these types from the history of painting?

Jonathan: Yeah. My images are representational, reflective of a body or an image like mine or the people that I know.

Your characters are usually not portrayed as static; there's always an abstraction.

Jonathan: Yeah, no one's ever fixed. Humans are variable and liable to change. It’s healthy and natural if you want to visit an emotion, a place, or role, if you want to be butch or femme. It's all drag, in a way. For me it's all a mask or a performance, depending on the person I’m with and the physical and mental spaces we inhabit together.

We're so used to seeing sex portrayed as dominant and submissive energies, when what’s happening is typically much more blurry.

Jonathan: It’s just filled with more possibilities. Abstraction for me is something more poetic; there are elements of the familiar, and other parts are less identifiable. For me that goes back to change and fluidness. I think that's really important. It would be weird to always have the same emotion 24/7, wouldn't it? If a person is permanently mad, that's not healthy! That's mental illness, right? So change is necessary and vital, and change without judgement or the fear of violence is really important.

It’s appropriate to have this conversation in your home because your paintings often highlight a gap between private and public presentation.

Jonathan: In private spaces, there's an unravelling, undressing, demasking of this other kind of honesty. But there's another kind of truth that comes with the violence and the uncertainty of being in a public space. There's a lot that can happen, and a lot that is happening, when you're not in a safe space or, in my case, a domestic space.

Do you change how you present yourself in public versus private?

Jonathan: We all do. In some way, shape, or form. Part of what's at stake is that people shouldn't be judged or face violence for choosing to be themselves in a public space. Whatever attire you're wearing or whoever's hand you hold, if you're wearing makeup, whatever role and mask you put on, you have the same right to walk down the street, the same as anyone else. What people do in their private and domestic safe spaces, it's their own business. But in public spaces, people have a work façade, a face that they have for this friend or that friend or their family, because we're each made up of different people. We all take on many different roles! I'm not trying to answer anything in totality, I’m just exploring possibilities and reflecting on myself and people I know. Sorry, I'm getting emotional.

Awe, no need to apologise!

Jonathan: I’m just painting from life, from the things that I deal with. I'm a human, so other people can relate to the regular experiences and emotions that I have. Art functions in many ways, but there are so many people who are like me, like you, like Will. We all bleed red, that's true, but at the same time all of our differences make us very beautiful and unique. It's important to understand that. If you want to call it poetics or abstraction, ambiguity, or whatever—that humans are beautiful and gross at the same time. You need both to be able to be a person.

You explore cultural paradoxes, like your presentation of the homo-thug. The cliché of this stereotype would be a man who's hard, who maybe has gone to prison, who is maybe involved in drug dealing, a king of the streets who presents himself as an alpha. In porn this type is often projected as the ultimate fantasy to be dominated by, but you show them being open to domination. Like the piece in your show at Company Gallery where the text read, ‘Butch in the Streets, Femme in the Sheets’.

Jonathan: I’m interested in both; both are authentic, along with the double consciousness of being yourself through your own self-perception and then through the expectations or the fear or desire of other people. This happens in a multitude of complex ways. There are many expectations of what it means to be a man, or a black man, of what's hard and what's soft. I’m presenting imagery or emotions that I hope balance those expectations and break down those stereotypes.

Do you have a moment or a piece that you consider a turning point in your work?

Jonathan: When I was diagnosed as bipolar, that's when my painting started to take on a different role and meaning. It became closer to me because I gained another window into myself. This allowed me to be more honest in my work.

In a way it’s the same as being gay: you have to decide if you want to come out as bipolar. It’s admirable that you’re open about it.

Jonathan: It's a part of me. I think that people appreciate the transparency. It's not something you can see, so to many people it's not tangible. I think it’s really important to destigmatise it within both the LGBTQ and black communities. Come look in here, in the bedroom. This is where I try not to work, but still work. This is where the other kind of magic happens. I like having my studio connected to the bedroom; it's really convenient for me.

Well, considering your subject matter, it’s necessary.

Jonathan: This way I don't have to commute to be at work and I can always keep an eye on everything. It's just all right there. I wake up and get right to work. What I paint is so about me and then not me at the same time. It makes perfect sense to have everything here together.

What do you do to take a break from making art?

Jonathan: It’s just about shifting gears. Most breaks involve working in other ways. I'll read, watch old movies, or go to galleries or museums. Philly’s museums are great.

Is Philly your hometown?

Jonathan: Yes. I was born in Mount Airy and grew up there, and then I moved over to near Cheltenham, near the northeast, during my teenage years. Then I’ve spent the past 11 years here in the Olney section.

Is this a rough neighbourhood?

Jonathan: In some ways it can be, but Center City also can be. The danger and uneasiness just take different forms. People around here are mostly friendly; they mind their own business.

You're 28? So you've lived here since you were 17?

Jonathan: Yeah. Me, Will, my mom, and my step-dad.

How long have you been boyfriends?

Will: We’re husbands. We were married on May 19, 2016. We've been together since 2011. I was 19 when we met.

I don’t know of many gay men that marry in their 20s. What made you decide to go for it so early?

Jonathan: I think there are different expectations about when heterosexual couples and gay couples should get married. Really, it just felt right, because we’re deeply, deeply in love.

Where did you meet?

Jonathan: We met through online dating on OkCupid. I had tried other online dating apps and dated lots of men from Philly. My heart was bruised and I thought I would never find love again, and then Will came along and swept me off my feet. I was pretty jaded, so when we first started talking I was really fucking mean.

OkCupid isn’t about quick sex. So you were both seeking a committed relationship.

Jonathan: Will taught me how much love meant to me. Before him I was so against it. He helped me figure out things about myself that I never knew I was capable of, like how soft and tender and how emotionally sensitive I am. I think that's what a healthy relationship is—an ability to better and enrich each other’s lives.

How did he sweep you off your feet?

Jonathan: For our first date, we went to Mandarin Palace on Chestnut St, in Center City. We had been talking online for two months, and it went from the dating app to the telephone to the webcam, and I finally built up the courage to ask to meet in person. He came to my studio, which was over on South Broad at the time, and the minute we saw each other we kissed. This is so mushy.

It’s really sweet. But considering the intense explorations of sexuality in your work, a love story and marriage is the farthest from what I expected.

Jonathan: I think that’s great, and funny. There are different ways a relationship can operate that may not adhere to mainstream expectations. Really, it’s just about being honest about what you want and what you're comfortable with. Just living your life, basically, without having other people's comments and judgements weighing you down. At the end of the day it's you and the person, or the people, that you want to be surrounded with, or that you fall in love with.

I think a big reason that relationships fail is because the people involved don't set the terms of the relationships themselves; they inherit the guidelines through religious or social standards because discussing what they really want and need is too scary, difficult, or abstract.

Jonathan: Absolutely. You have to keep all that noise out of your head and out of the space that you have with your partner—one partner, multiple partners, whatever that dynamic is of those wants and needs that the people involved set up for themselves. You just have to really be honest, and you have to be vulnerable to take that kind of risk.

Will, are you also an artist?

Will: No, I studied social work and early childhood education. But right now I model for Jonathan and also for the Fleisher Art Memorial. And I take care of, look out for, and just enjoy being with my spouse.

Jonathan: He makes sure this crazy train stays on the right rails.

Looks like he’s doing a great job. Did you think you'd end up with an artist?

Will: When we met I didn’t know much about what an artist is or what they do. I'm mostly attracted to the goodness in him. It's just all about love.

Jonathan: Having the courage to be yourself—for yourself, and then for other people—is necessary but not always easy to do. It takes a certain bravery and commitment to unapologetically be yourself.

What is it like to be a young married gay couple living with family?

Jonathan: It’s great now because my parents are so down to earth, so present, and have become so accepting of me as a queer person and as an artist. When I first came out, at 16, it was really traumatic.

That was about 2006? Almost a full decade before gay marriage was legalised in 2015.

Jonathan: Yeah, at school only a few people teased me, but it was more about being overweight than my sexuality. Some kids were already out, so I didn't feel alone. Representation is mega, vitally important—to see kids in older grades than me, seeming like they're happy, making progress, having friends, and just living a regular teenage life. That really helped me when I got to the point of deciding to come out. I feel like I was blessed to not have such a traumatic time at school. My trauma lay in other places.

At home?

Jonathan: Yeah, I was raised Christian Baptist. As I've got older, I've understood that my mom’s and grandmother’s initial reactions weren’t about thinking I was unworthy of life or beauty or anything like that. It all boiled down to their fear that something bad would happen to me. My mother is 54, and her generation still primarily associates homosexuality with the AIDS crisis. When I originally came out to my mom, it wasn't good for either of us.

So your parents are very involved in the church?

Jonathan: At the time we all were. I went with my grandmother and my parents to church every Sunday. I was even an usher. My grandmother lived with us until she passed away earlier this year. The church gave her so much pride, joy, and a sense of belonging. So she took it pretty hard when she found out I was gay. She started off telling me, ‘If you fuck men, you’re going to die, and I love you too much for that to happen’. But after some time she came around. She eventually said, ‘You're my favourite and I love you very much and if this is who you are, then that's OK with me!’ Not to get Maya Angelou about it, but I think love really has the power to liberate and to heal.

And your step-dad?

Jonathan: He took it the best. He just said, ‘I love you as a son, like I always have’. He was an ear for me when I needed to talk through the issues I was having with my mom. His advice was simple: ‘Stay in school, don't do crack, and practise safe sex!’

So you never left home through all that tension?

Jonathan: Well, for one, I didn't have any other place to go. And then I was scared of every fucking thing! And then I was like, ‘Well, she's not kicking me out, so—’. Even some cousins made homophobic remarks about me. That made it real to my mother on a different level. It amplified all her fears. In a weird way, all of this helped us grow closer, if that makes sense?

Well, yeah, even though it must have been hard it definitely makes sense that the whole process would have given you all many opportunities to understand each other better. And in the end you were more important to your mother and grandmother than their standing in the church. Even though your paintings are doing the devil's work in her home.

Jonathan: A lot of my friends have had really bad, strained relationships with their parents after coming out. My mom was open to learning, and because she's inherently a loving person, that love allowed her to not let organised religion get in the way of our relationship. Now she comes to openings with us. We even watch RuPaul together. She still has her faith, thank God, but she's not really that connected with the church anymore. For her there was a transformation, which I think is really beautiful.

And so how do you feel about the idea that this chapter of your life is over? Is your mom sad that you and Will are moving out?

Jonathan: She’s excited to design our new place. She wants to make everything metallic. As a matter of fact, she's really good with interior design and home improvements. She loves Christopher Lowell; we bonded over him when I was younger. He’s had a few makeover shows: Interior Motives and Work That Room. I even have the book.

‘Moroccan Mystique’! He loves a themed room. I see his influence in your living room downstairs. What is it that you both like about him?

Jonathan: He takes a space and really unlocks its potential with his power to transform it. But he also creates enough space for storage, because we have a lot of shit. And he’s also so good at setting a mood. He’s sweet and has lots of positive energy.

Just like you. It’s been quite an amazing year for you. Do you have any closing thoughts?

Jonathan: Well, I’m just so happy with my life right now. It's a really scary time to be alive in a way. But then also a really, really beautiful time to be alive. It's sort of electric, anxiety-filled excitement. People are getting fed up with people’s bullshit, their racism and homophobia. It's a beautiful way to protest, by being yourself. It's really loud and wondrous, all the changes in representation that are happening right now. There are gay people on TV, there's RuPaul, there are black superheroes in Black Panther. I’m really excited for the generation that is coming up now. I mean, even with fucking Trump, I feel like honest, hardworking, loving people will always find a way.