JERRY SALTZ

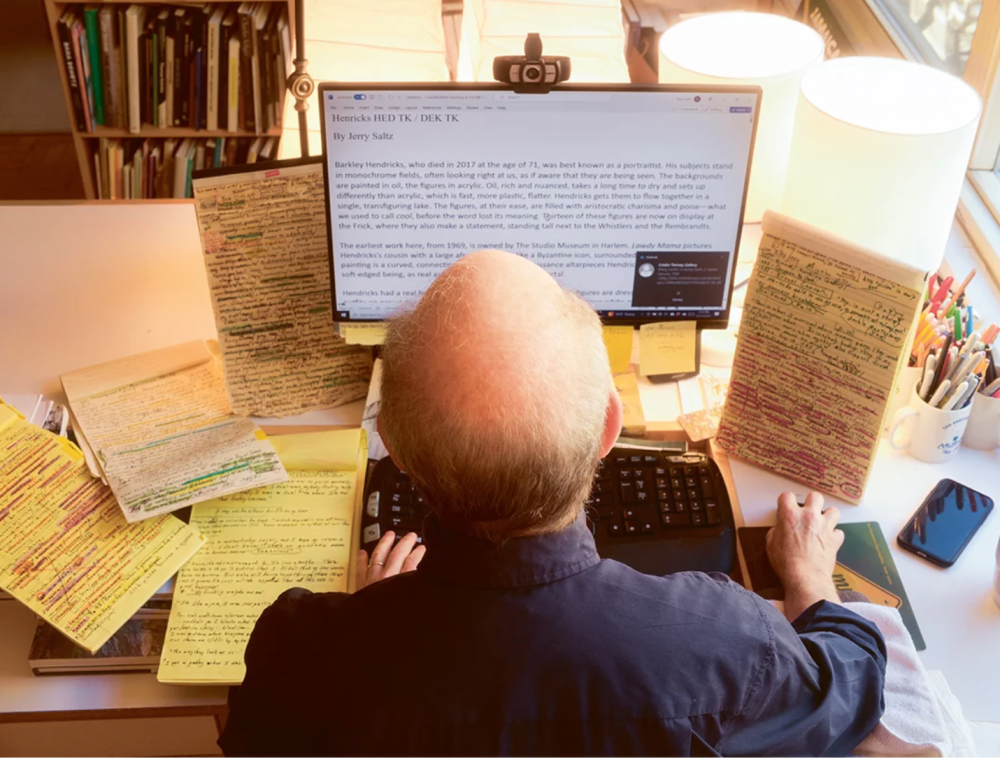

Jerry Saltz lives an extreme lifestyle. The majority of his time is spent on deadline. His days are split between seeing art exhibitions and writing about them. He attends over a thousand per year and has been at it (professionally) for 32 years. He’s become a star art writer for ‘New York Magazine’ because he’s dispensed with the intellectual pageantry and pretension so often associated with his position, and unlike critics before him, he’s brought informality to the field through his trademark can dour, humour and self-deprecation. He’sscaled an elite profession but managed to stay true to his identity as a man from a working-class background who became obessed with visual art. I’m meeting Saltz to go gallery-hopping, starting off on east Canal Street in the area now known as Dimes Square, on a bright, crisp December afternoon. Despite this being our first meeting, his ease and warmth give off the feeling of being with an old friend.

Before he was a critic, Saltz was an artist himself. In his teenager, his interest was fostered at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History where he was drawn to Navajo sand paintings, Oceanic art, and Swedish visionary Hilma af Klint. “All this work felt driven by innate spiritualism and inner necessity, as opposed to the abstraction coming out of New York,” he wrote in his 2017 essay ‘My Life Asa Failed Artist’, a soul bearing retelling ofhis career trajectory. He was drawn to works that had mystic functions: “I loved that it was all for more than just looking at: It was meant to cast spells, heal, protect villages from invaders, prevent or assist pregnancy, guide one through the after-life.” When he decided to become an artist himself, it was for more pragmatic reasons: “In high school, when I looked around, the only people having sex at my school were actors or artists,” he tells me. He had great early success, opening a gallery named N.A.M.E., organising 75 exhibitions and two solo shows, being interviewed by legendary art critic Peter Schjeldahland winning a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. He eventually moved to New York City where he showed his work at the first incarnation of the Barbara Gladstone Gallery, the powerhouse institution whose current roster includes Richard Prince, Rosemarie Trockel, MarkLeckey and the estates of Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe. But for Saltz, this enviable start to his art career only had a miserable effect. “I just heard demons say to me, ‘You don’t know what you’re doing. You don’t know art history. You have no degrees. You never got an education. You can’t schmooze. You don’thave money. You’re from Chicago. You’rea fucking loser.’”

The voices dominated Saltz’s thoughts to the point where he could no longer make work. He quit making art and became a long-haul ten wheel truck driver, moving art and furniture. But he stayed part of the artworld. He would spend two weeks on the road in solitude, followed by two weeks going to openings, being part of the social life and maintaining a small professional stake. It was an almost decade long period that made him both anxious and envious. Then 1989 marked the end of his exile after he fully accepted two facts of his life:

1) He was not an artist.

2) He still loved art.

Without having written a word, he had aninstinct to participate as a writer. Through his friend Jay Gorney (of Jay Gorney Modern Art), he was recommended to editor and curator Richard Martin and was offered his first chance to write for ‘Arts Magazine’. He convinced Martin to give him a column devoted to one work of art per month. For about two years he wrote in a “very good first person voice, but those were essays, not criticism, and then they closed down.” In his second post, at ‘Art in America’, he wrote overly intellectual pieces that were well received, but empty. “It turns outthat I didn’t know what I was writing. If you asked me, ‘Do you like the work?’I didn’t even know. I was creating a screen. Then—Wow!—I was delivered by what delivers all of us: the deadline.” Saltz prided himself on turning every assignment in on time, and once, when he was running behind schedule, he submitted a dashed off text that was loose and honest, a review that showed how he felt and who he really was. “That was the day I understood that all I have to do is write in my own voice and I can be free. And from there, I just kept writing.” Fast forward to 2018, when Saltz was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his criticism, the jury heaping particular praise on ‘My Life As a Failed Artist’.Saltz’s unexpected, explosively successful late career as a critic surpassed his wildest expectations. “I some how pulled myself out of a tailspin of rage, loneliness and lack of purpose,” he says. He failed big before he succeeded big, and now he views everyday as a gift. This unusual personal trajectory gives his consistent encouragement of artists the warm glow of authenticity. His restless output as the senior art criticat ‘New York Magazine’ since 2006 has seen him share the joy and empowerment that art gives him with his readers. He’s proud to tell me, “I consider myself maybe the 11th best art critic, but I’m the most read art critic, and I can take that. I think of myself as a folk critic.”

Saltz on Wolfgang Tillmans:

"Over the course of his 36-year career, the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans has created what I think of as a new sublime. His work conveys that the bigness of it all is no longer in God, the ceilings of the Renaissance, the grandeur of nature, orthe all over fields of the Abstract Expressionists. Tillmans intuited that the sublime had shifted, had alighted on us.”

Saltz on Refik Anadol:

“‘Unsupervised’ has the virtue of not disturbing anything inside you; it triggers no mystery. With all due respect to Kuo (the curator responsible for this pointless museum mediocrity), it has neither dreams nor hallucinations and takes away art’sotherness. In this hypercontrolled, antiseptic setting, art and doubt maintain separate bedrooms. It’s like looking at a half-million-dollar screensaver.”

Saltz on Dana Schutz:

“Her latest solo endeavour at David Zwirner, ‘Jupiter’s Lottery’, features a tainted artist who seems eager to plant enormous stakes in art history. Her more ardent paintings left me speechless: huge, luridly iridescent moonscapes, slathered surfaces piled up with greasy paint, giant marionette-like figures with spidery limbs and oversize heads. Her ambition is massive, Kiefer like.”

A few days before our gallery tour, I conduct an informal survey about Saltz at a pent house party packed with significant players in New York City’s art world. I ask them how they feel about the critic. The responses typically start off catty, with one famous painter quipping, “Did they run out of fantastic men at Fantastic Man?” Then they explain their take on his criticism, or how it’s impacted them. Then, inevitably, they start to roll back, offering a follow-up statement that softens their original blow. “Although, he’s a really nice guy” is the typical sentiment. What does this mean? On one hand, very little. If art critics do their job well, they’re bound to make enemies. And Saltz is clearly doing something right, because since he began writing about art in 1989, he has become one of the most visible critics in the world, guided by a straight forward philosophy he articulated in a 2008 interview (for Sarah Thornton’s book ‘Seven Days in the Art World’): “I’m looking for what the artist is trying to say, and what he or she is accidentally saying, what the work reveals about society and the timeless condition of being alive.” Whilst the art world elite’s dislike for an art critic is par for the course, Saltz isn’t here to serve them. Instead, his words lead a mainstream audience through the overwhelming matrix of contemporary art, and they come at you with the full force of his confident, eccentric personality. He’s not so much a kingmaker as a hypercharismatic, idiosyncratic tour guide.

Before I meet Saltz at Club Rhubarb, an artist-run gallery that’s taken up temporary residency at 1 Ludlow in Dimes Square, I see a stylish woman in her early thirties accost him on the street. She has major fangirl energy. At first glance, the encounter looks awkward and my instinct is to rescue him, but then I take it as an opportunity to observe how he handles an occupational hazard: artists relentlessly pitching themselves to him. Once he realises it’s me, he introduces me to the artist stranger with the charm of someone hosting a cocktail party. The artist dives into a story about how important her initial encounter with Saltz was to her. It was five years ago and she’d recently married a rich man and was paralysed by moral conflict about the transition from struggling artist to artist-with-considerable-resources. She recaps Jerry’s advice: “You told me everyone has their advantages inart. Some people have family members who were established artists. There’s a lot of nepotism. You can just be at the right place at the right time, and for the longest period of time, being white and male and just showing up at the Cedar Tavern was enough. Everyone’s working with their own advantages, and you told me I shouldn’t be afraid of using mine. It was really helpful advice.” With genuine curiosity, Saltz enquires further. She’s now a divorced mother and an out lesbian whose work has changed dramatically, along with her new circumstances. His tone is upbeat, supportive. “Do we follow each other? Let me show you some Instagram love,” Saltz says, motioning to her to embrace him for a photo. There’s zero gatekeeping: without knowing the artist’s background, her politics, or much about her work, Saltz’s own social mediabrand endorsement is readily offered up. He’s happy to share his image for her to capitalise on. It’s an unusual amount of generosity from a man of his prominence,and it demonstrates how he’s become an unlikely influencer, with nearly 700,000 Instagram followers. Tony Cox, Club Rhubarb’s energetic owner, lets us into his gallery, a flexible space that celebrates artists who began their careers outside academic structures. He set it upin 2018. Before that, in the mid ’90s, Coxwas a pro skater, and in the ’00s a showing artist. Cox has organised an ambitious exhibition titled ‘I Was Only Dreaming’, which features over 60 artists and takes upthe whole four-storey residential building.The showman thrives on sharing his artists’ personal narratives. With a rapid-fire bravado, he entertains us, spinning elaborate backstories. Saltz looks overwhelmed but clearly engaged.One work evokes an immediate reaction: “That’s fucking great!” he exclaims, pointing to a diptych. On one side is Mona Lisa being painted, on the other are three naked men strapped to a bench in a sex club, asses red, presumably from being spanked. "men strapped to a bench in a sex club, asses red, presumably from being spanked."

The piece, ‘What’s With The Smile, Mona?’, was made by Sal Salandra, a 78-year-old former hairdresser who does elaborate, painstaking BDSM needlepoint “paintings”. “Please take a picture of me with this work,” Saltz asks, striking his signature art-selfie pose, thumbs up, relaxed smile, wide eyes. He playfully endorses the art, not taking himself too seriously. “Let me know if there’s anything else you’d like me to pose with,” he says to Cox, ready to lend his influential image in support of the art that excites him. On the next floor, Cox shows us an enormous 3D knit sculpture of two naked figures sprawled out on a bed. Neither of us have seen high-tech knitting applied to sculpture before. Saltz touches the piece, like a baby trying to understand the world. It strikes a chord. He asks for details: Who? What? How? Cox fills us in: the piece was made by Felix Beaudry, it’s titled ‘The Glob Mother and Lazy Boy on Bed’ and the production process uses new technologies. In the friendliest way, Saltz barks at Cox: “Send an email to Roberta right now! Say Jerry told you she has to see this show.”

Roberta Smith is Saltz’s wife and until very recently was the co-chief art critic for‘The New York Times’. “We met in 1986. She’d been fired as a critic at ‘The Village Voice’ and I hired her to write an essay for a book. I hadn’t read her—I’m a bad reader—but I knew she had a name and I thought she was hot. We started talking, we were sort of dating, and since then we’ve never been apart,” Saltz explains. There aren’t many couples whose combined professional reach so significantly influences an entire segment of culture. Since they married in 1992, both have been working at the top of their field, offering their own unique perspectives on how to view and value art. “Roberta and I are the absolute last people of our kind: weekly critics writing for a publication. We see 25 to 30 shows a week. We’re from a bygone era where you could see the whole art world in two or three days. Everything! Now you can’t do it ina month. It’s impossible. But we still do it, ”he says. Why should the show at Club Rhubarb go to Smith instead of him? Hebreaks it down simply: “It’s a great show. She’ll love it and she’s a much better critic than I am. If she’s interested in an exhibition, I immediately give it to her.” That evening, Saltz’s Instagram post appears with the lead image of Beaudry’s 3D knit sculpture. The text reads: “A few crappy pics from a great three-floor (!) group show sort of a biennial of the Lower East Side Dimes Square (I hate the designation too) ethos. At @ronlittles @clubrhubarb at One Ludlow. The first few pics are of a kind of unbelievable formal leap in knitting by @stinky.felix... A large machine that one programs and that then knits these figures into patterns which the artist, I assume, sews together and stuffs. This trans couple in bed is mindblowing even if the pics don’t capture it.” A month later, Smith’s review appears as the New York Times Critic’s Pick, titled: ‘On the Lower East Side, a Secret Space,a Mini-Biennial.’ Smith praises the show, writing: “The art, the building and the square fit together like nesting dolls ,demonstrating that in this time of gleaming big box galleries and global franchising, Manhattan still has patches of grassroots and D.I.Y. All that is needed is an artist who believes that the work of other artists deserves to be more visible.”High from the energy of the first show, we walk towards our next exhibition. Saltz spells out what is already abundantly clear: “You know, I just love looking at art. It gives me so much life and so much information. If I see one good thing in a show in a day, I consider that a great day. ”Together we take in two more exhibitions, increasing the odds of making his goodday even greater. One is in Chinatown, anarea that’s been flourishing in the last five years, populated by small experimental galleries. A space named Situations was one such pioneer. Here, Saltz is floored by an ambitious fountain containing ink instead of water. Again, he sneaks a touch, trying to understand the piece with his hands. Jackie Klempay, the gallery owner, explains that it’s a self portrait of the artist Ellen Jong, standing naked on a platform, squirting her breast milk (black ink) into a circular basin. It splatters on impact, slightly staining floors and walls. Posing for another art selfie with the fountain,he ponders the piece out loud, trying to grasp what to make of it. “It rises above the moment and speaks to the moment somehow... How is it speaking to the moment?” He pauses. Klempay and I are both waiting for a philosophical assessment. “Everyone loves boobs.” We all laugh.He goes on. “She’s giving you permission to look at them. They’re life-giving, but also these are poisonous, and also there is this total artificiality. And it is a focal point... Good job... I’m sure it’s not easy to sell this?” he asks, with genuine concern. “We sold one at Art Basel last week! Not this piece, but another self-portrait ink foun-tain from this series,” Klempay says. A few doors down at artist Jack Pierson’s newproject space, Elliott Templeton Fine Arts,we view some cheeky text pieces by thelate British artist David Robilliard along with elegant, straight forward portraits by another Brit, Alessandro Raho. Saltz has seen the show before, so he is more interested in how the young gallery attendant, Evan Lincoln, found his first experienceat Art Basel. “You have to sell things. It’s not a profound realisation; it’s just that atthe fair, the mechanics of the art world arelaid bare,” Lincoln explains. Saltz counters with his unexpected take: “It’s a condition. It’s an event that has to happen. It’s a way to participate in a system that we hate but to take a chance and make some money. So I don’t go. I would lose my mind. I’m lucky, I get invited everywhere, but I don’t have the social make up to leave my hotel room. So if I went, I would be sitting in my window in Miami just crying every night, thinking about you guys having fun and wondering, ‘What am I doing here?’”Saltz and I are starving, so we hit the neighbourhood hotspot, the Corner Bar at the 9 Orchard hotel. At 3:30pm, it’s empty except for a table of well dressed twenty-something women at their photo agency’s work lunch. Their heads crane when Saltz walks into the dining room. They invite us over to their table. “Hello ladies, I’m Jerry Saltz.”

“We know who you are,” they giggle in unison. “You’re the guy from Instagram.” The interaction has the energy of a celebrity

sighting. It’s another reminder of how powerful a tool social media has become for the 73-year-old. As we wait for burgers and fries, I ask if he could identify the starting point of his social media fame. Saltz recounts a big breakthrough. “A freeing moment I had was around 2010, when Facebook was a very big thing and people would write their status: ‘I’m going to the dentist.’ One day, for no reason, I wrote something negative about Marlene Dumas as my status. Something like ‘The work seems to have plateaued. She seems to be just reproducing painful photographs. It’s pain porn.’ I went about my day and when I came home there were a thousand comments tearing me a new asshole. I was in shock. Not that I’d said something so wrong and disagreeable. That didn’t matter. I had a vision of the-one-speaking-to-the-many, which was the model of art criticism that I came into. I suddenly understood that that wasn't my voice. I could never get that authority. Instead, I accidentally found a way that themany could speak to one another acrossa more horizontal platform. I found a way to have a conversation, make mistakes alive, correct myself, and reassert myself. I learned to argue. I learned to defend. Ilearned to listen. I really, really learned to listen. And that was enormous.” Around that same time, Instagram launched, and Saltz jumped in headfirst, knowing that the new platform would be ideal for an art critic, even if the rest of the art world didn’t know it yet. “I made it onto some stupid ‘100 most powerful people in the art world’ list, and they warned me that if I kept trying to practise art criticism online, I would never be on a list like that again. I thought, ‘They can kiss my ass. Goodbye, you motherfuckers! I don’t care any more.’ I suddenly had another layer of freedom. I became a freedom machine and I just started doing whatever I wanted to do. I’ve made mistakes and I’ve been spanked for them. ”Besides his criticism for ‘New York Magazine’, his opinions can be found splashed all over his Instagram. There he unpacks his delight at and his interpretations of artists’ accomplishments, and he never shies away from exposing aspects of his personal life: anxieties, desires, politics and food habits, including his extreme coffee addiction. He’s a populist art critic who holds significant power but doesn’t wield itin conventional ways. He’s not afraid of criticism or controversy, often pushing things to their limits as a way of articulating the boundaries of his public persona. He’s comfortable swerving outside his laneinto subjects like sex and politics. So much so that, at times, he’s been better known for posting erotic art or relentlessly hating on Donald Trump (telling his followers to shun anyone who voted Republican, including family) than for his art writing. In 2015, he was temporarily grounded by Facebook for posting hundreds of images of genitalia from ancient Roman and Greek art and medieval manuscripts. The complaints were not from red state conservatives; instead, it was friendly fire, coming from his own followers, many of whom were artists and curators. It was a turning point for Saltz. “I got very defensive. Then my wife said, ‘Why don’t you believe people when they tell you they don’t like something?’ There’s something there. What I did was, I changed. I won’t post women’s bodies any more. I’m a hopeless heterosexual, or remittent or whatever. Now I only post dicks, ass and balls, but to this day people refer to me as the guy that posts tits, and I just have to accept it.” For someone who was enjoying being an invincible freedom machine, it must be hard to have to self-censor.

But the many other ways he uses the platform to shock, educate, reassure and rally areundeniably among Saltz’s greatest power sand biggest pleasures. In the months after we first met, he shared over 100 compre-hensive multi-slide posts to his grid, all demonstrating his excitement for hundredsof works of art. People respond online but also in person. When we said our goodbyes to the fangirl artist earlier, he told me, “That happens everywhere I go. And it’s healthy. On the streets the response is wild. I take two 40 minute walks per day to decompress, and people approach me. I say, ‘Let’s walk a block, tell me what’s onyour mind,’ and they get right to the point about art, life, whatever.”

“You never get annoyed with that?” “No, I love it. It’s fun,” he says, convincingly. Saltz has entered the canon of iconic New York City writer-editor personalities, along side Fran Lebowitz, André Leon Talley, Ingrid Sischy and Tom Wolfe. He holds that space not due to glamour, money or power but because of his boundless, affirming passion for art. “I love my life. Every day...everyday I think about how goddamn lucky I am and how fucking close I came to being a working stiff and not having art be part of my consciousness. Not having the art world, which everyone hates, but I adore,” he says. “This is my family.”