CHRIS SCHANCK

Interview by Michael Bullock

Portriat by Chris & Michele Gerard

Images courtesy of Friedman Benda

Pinupmagazine.org, 2018

THE INVENTOR OF ALUFOIL PAYS HOMAGE TO THE GARDENS OF DETROIT’S BANGLATOWN IN HIS FIRST SOLO SHOW

Ever since Chris Schanck was a student at Cranbook he has been experimenting with processes and aesthetics, inventing his own distinct design alphabet. At its core lies his famous low tech “alufoil” technique in which the design alchemist maximizes the potential of forgotten everyday materials — mainly packing foam and tin foil — and seals them with resin, literally transforming one man’s trash into another’s prized possession. Schanck’s aesthetics embraces the bravado of science fiction and finds optimism in the dystopia of his hometown Detroit. Now that his vocabulary has been firmly established the artist is ready to start telling complete stories, and this month is a particularly exciting moment in Schanck’s career. On March 1, 2018, Unhomely, Schanck’s first solo exhibition at New York’s Friedman Benda gallery, opened to the public. For it the 42-year-old challenged himself to push beyond his signature process, employing it to create his most ambitious, personal, and most narrative work to date. The breakthrough piece is a haunting shelving sculpture that pays homage to the gardens of Banglatown, the nickname the Bangladeshi immigrants have given their neighborhood. The overall result: a collection of radical functional sculpture that gracefully walks the razor thin line between homely and seductive. A few days before the opening Chris and I got together for a FaceTime video walk-through of his new Detroit studio.

You’ve been building a whole little world for this show. Was the approach different than when you create individual pieces?

Totally different. The gallery was really supportive and encouraging me to do whatever I wanted to do to explore this body of work to its full potential. First I went back through all my sketches, back to the ideas that I have always wanted to see realized that I could never make for clients. I sketch ideas for figurative pieces all the time, but it's not like a client is ever going to ask “Can you make me a kneeling man side table?” (Laughs.) So for this show I’m taking the forms that I've been dreaming about making for a long time and bringing them into the body of work. It’s fun to finally explore all of that.

Is that the point where we find out what you really want to say as an artist?

Yeah, no pressure. (Laughs.) It’s terrifying but exciting at the same time.

While Chris walks me through the studio he shows me a table, called Gold 900. The base is a gold man made of sticks, the table’s flat top looks like a resin dipped atmospheric shot of the earth.

Wow! A woodland gargoyle version of Atlas!

He’s made up of all these bits of wood and sticks. The guy that lives across the street from me that runs a non-stop, garage sale. He collects really interesting bits of wood and sells them to me. The figures foot is a single rooted knotted piece, his hand is a single root.

How did that piece begin?

I've been drawing figures, snakes and monsters for a long time. It was about figuring out the right one to do for this show. To visualize them I had two assistants dress up in garbage bags and try different positions. To see how's the shapes would work in space. I ended up going with a subordinate pose, which became really interesting with the material. I used all the collected sticks and bits to fill him out. Now he doesn’t feel subordinate but humble. The materials are super common but then he gets the Midas touch, finished in gold. So he's fantastic but simple at the same time.

He’s carrying the weight of the world.

Precisely. It's really beautiful when you see it in person because the layering on the tabletop creates so much depth.

Your new studio is impressive. It looks so much bigger than the first time we met in 2013 (see PIN–UP 14).

It’s five times the size. Now we have stations for each of our processes. They’re constantly being filled and changing. This is our show wall. I put up a name game challenge. If you title a piece or put up a word that inspires the final title, you get a gift card to the bagel/coffee shop. There’s some pretty funny stuff on here for one of the newer pieces. Some say to call it Barb, Janet, Crow, Menagerie, Shanti, Fraternity Down the Yellow Brick Road. There’s some really good shit.

Which name’s winning?

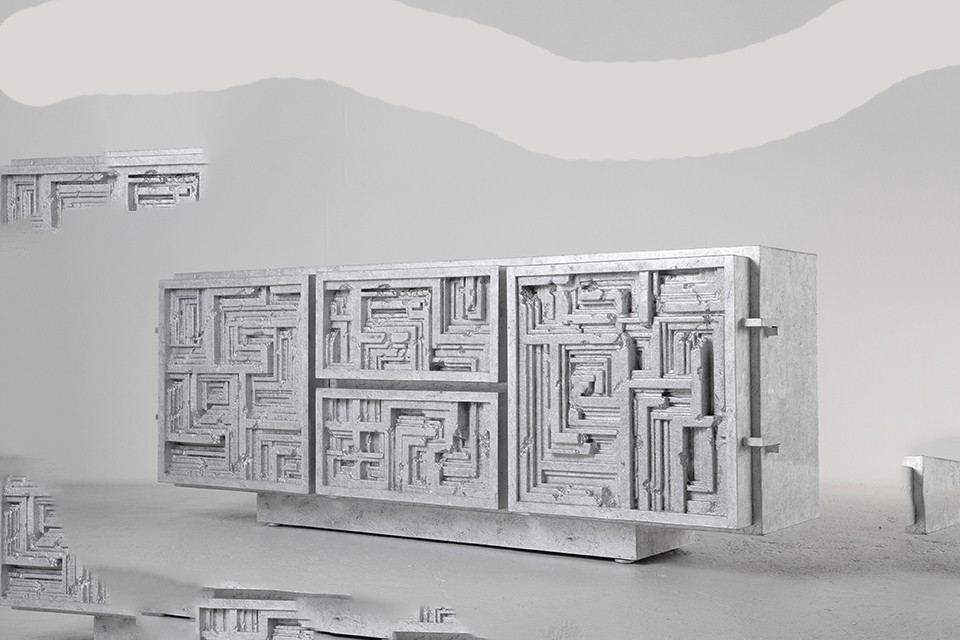

Right now I’m winning this one but nobody likes it because I want to call it Twilight. I was thinking Twilight Zone but of course everyone else is thinking of the vampires, which I'm also okay with, but I’m still getting a lot of pushback. One of the members of the studio, Connor, won this one. (Points to a silver sideboard.) It’s a credenza named Oubliette, which is a medieval dungeon with a hatch only at the top.

How do you determine who wins?

I go through the list and talk with each person that offered a name. I find out where it comes from, what it means, and see if it rings. For Oubliette, we discussed the name during the design process. Connor’s really into Dungeons and Dragons, so there’s a lot of references to magical, spiritual fantasy. This one we all named together is the coffee table. It’s called the Scrying Table which is sort of like a magic mirror. When you look into it you can see the future; who’s betraying you; when the enemy’s coming; that kind of thing.

A very useful table. What’s that incredible piece? It looks like a children’s fort.

This one I’m probably most excited about. For a long time I wanted to figure out how to talk about the community that the studio is a part of here in Detroit, and how inspiring it has always been to me. All the decisions in this piece are specific to my neighborhood. People here have an intuitive way of building and it’s developed into a style that’s unique to the area. As a result all the gardens here have these DIY structures. That’s where the scarecrow comes from and all the boxes and all those textures. The working title is Banglatown (It also ended up being the final title), which is also the name of the area where my house is. It was always a nickname, but the Bangladeshi community sort of officially-unofficially gave our area that title, they even put up a “Welcome to Banglatown” sign. (Laughs.) I’ve been collaborating with women from this neighborhood who make the scarecrows for her families and their neighbors’ gardens. We’ve made so many iterations. The scarecrows are terrifying and gorgeous at the same time. It was an important element to include.

The Banglatown piece feels like the anchor for the show, very different from any of your past work.

Yes. Someone described it as apocalyptic but it isn’t. This is the most optimistic thing I have ever made. It’s about growth and self-reliance. It’s a hopeful image. It’s a symbol of how to thrive on the edge of the apocalypse.

It’s also a strong metaphor for your own studio and how it has grown. What’s your process like now in your new studio? What’s changed and what has remained the same?

We definitely got more efficient. For this show we grew to about 25 people. There are about six leaders that manage different teams. There’s basically peer-to-peer learning within those teams. At this point their skill level is far beyond my expertise.

That’s an incredible phenomenon: you taught your self-created techniques and then the team that’s executing them has further developed and refined the process?

Yes. It’s brilliant, and it started happening purely out of necessity. But early on I recognized its potential. The ability and the confidence of the group as a whole has grown. There’s a much larger collective understanding. We can move in and out of phases and deal with problems in a way that’s more and more like an ecosystem; it’s no longer me running around telling everybody what to do. And those outside of the studio are important too, whether for new techniques or if they’re the master upholster or welder or glass artist that we work with. There’s this whole outside network and those relationships have been built over the years and now they have turned into friendships. There’s a sense now that everyone is respecting and understanding everyone’s roles and no one is more important than any other, which makes for a Zen way of producing. We started in my house, in an environment that was very intimate. We had to build respect and understanding and trust and a sense of what we were doing personally and professionally before we scaled up. Anything that's really interesting that happens now is definitely a collective experience, not a single person’s vision. At the end of the day it may have my name on it, but it’s a little community that makes it all happen.