ANDRÉS JAQUE

ON IMAGINING URBAN DESIRES

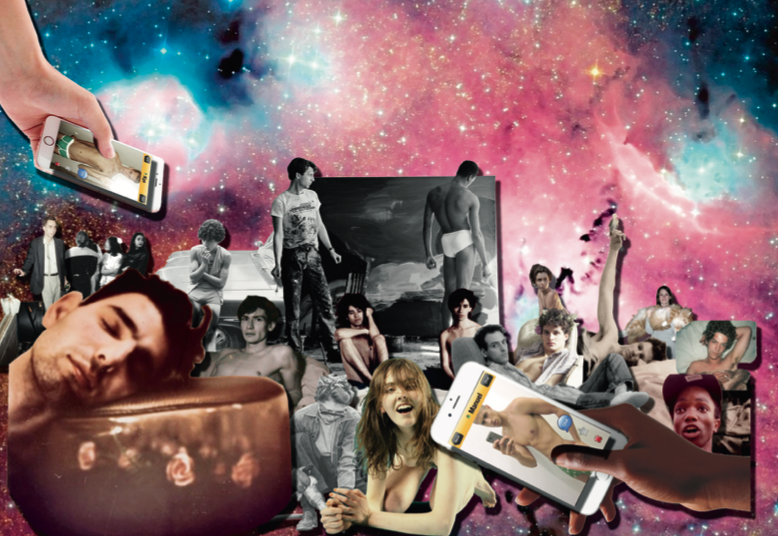

It may be jarring to hear it, but 2018 is the 20th anniversary of Sex and the City, HBO’s runaway hit show whose first episode aired on June 6, 1998. The series unexpectedly became a major defining force not only in contem- porary culture but also in urban development — that is according to Andrés Jaque. The fast-talking and hyper-charismatic Spanish-born architect, principal of Office for Political Innovation, is interested in how recent popular media — specifically Sex and the City and Grindr — have, in their own way, synthesized the conscious and subconscious desires of vast segments of the population, giving them form and creating collective fantasy spaces. Interrogating this connection, Jaque and his team first undertook a survey examining the socio-spatial effects of Grindr which, since its introduction in 2009, has quietly revolutionized the sexual pursuits of gay men. After exploring the dating app's effects on the urban imaginary, Jaque spent a year studying Sex and the City’s real-world impact on the built environment, especially in Manhattan, and then aired his findings in the recent exhibition Sex and the So-Called City, which was on view New York’s Storefront For Art and Architecture. Jaque explains to PIN–UP the pervasive influence of Grindr and Sex and the City and why he feels it’s absolutely essential to analyze and understand their respective impacts.

How did Office for Political Innovation end up making a short film about the history of Grindr?

Last year, when the Design Museum in London moved into its new venue in Kensington, they asked a handful of designers what their favorite piece of design is. The one thing we thought was radically relevant was Grindr. We’d already been doing research at the Grindr headquarters in West Hollywood — they provided us with access to their archive, and we interviewed their team. It confirmed for us what we already suspected: Grindr isn’t just an app, it’s really an arena.

What would you say is its most significant purpose?

Grindr produces a kind of collective brain. In a literal way, it catalogues, archives, and presents the fantasies and the neuronal dimension of individuals in an online space that overlaps with daily lives.

What impact does that have on the built environment?

Grindr plays a fundamental part in rendering the space of gay men into a lifestyle bubble, destroying gayness for many, closing public social spaces, removing political activism, removing queerness from gayness. It renders gayness as a stylish milieu where brands can circulate, where respectability is produced. That’s having a direct effect on cities like London and New York. Many gay spaces have been replaced by “luxury” apartment buildings. During our research into Grindr, we found out that the places where super-expensive new condo towers are built are the number-one locations where Grindr users switch on their apps. Their goal is to end up in those apartments. It’s a very direct removal of queerness from cities, which is being replaced by consumption.

Grindr took an individualized experience that was self-defined and amorphous and gave it a limited common vocabulary so that all its members now see gay identity as fitting into a bunch of organized labels, and now that we live within that structure, it has defined our experience of being gay men?

Yes, exactly. And as a result, there were big transformations. Conversations on Grindr are one-to-one. Gayness is changing from a collective experience to a one-to-one thing, unlike in the 1980s, for example, when HIV activism produced a huge sense of community within LGBTQ sectors of society. We cannot deny that Grindr is amazingly effective in allowing men to meet each other easily. The app is used in almost every country in the world, although what it means in New York or London is different to what it means in Saudi Arabia or Egypt.

Your film also presents Grindr’s unintended uses, for example how it was used during the 2015 refugee crisis.

Yes! Incredible. Men from Syria used it to navigate Europe and European members used their profiles to advertise that they were willing to help Syrian refugees on the move. They provided them with shelter and information, they helped them seek asylum, and introduced them to lawyers. All that humanitarian activism was moved by and mixed with sexual attraction.

You must be the first architect to examine Grindr’s consequences.

But I’m not criticizing it. Grindr is the space where many developments and interactions in our culture are happening. Grindr is the space we inhabit now, so we have to start discussing it and operating in that space. Public space is not the same as it was in the 1960s or 70s. Political interaction is no longer primarily on the streets. Our porn, interior design, fashion, and bodies are where political struggles now find an opportunity to occupy space, and it’s our role as architects to make sense of that. I consider that our mission.

Does that mean creating digital spaces? Or do you translate those findings into IRL built projects?

It’s about collaborating with the actual people that have a voice in the making of this environment that we’re all a part of. Grindr, Cocky Boys [a gay Inter- net porn-production company], and Pornhub were not produced by a single person. They’re a concurrence of many different forces.

Is it true that you’ll be designing sets for Cocky Boys videos? And if so, how did that happen?

Yes! We always spend 60 percent of our resources and time doing research — going to where things are happening, meeting people, talking to them, exploring their archives, so we can understand what they are doing. We end up finding oppor- tunities to have a say in those processes because we’re there, at the beginning. Architecture has traditions that are also very useful for people who are operating in other forms of urbanism.

Speaking of other forms of urbanism, tell me about your show Sex and the So-Called City.

It all started with a project called IKEA Disobedients [2011]. It was a moment when IKEA was advertising that they were providing the tools for people to turn their homes into independent republics. For us, this was something to discuss because homes can never be an entirely independent republic. So we developed an archive of the different ways people used IKEA to make their homes collective spaces. We were surprised to find out that most of the activations we discovered had to do with the body, to do with sex. That was the beginning of a discussion about economies and interpersonal relationships. We spoke with elderly people who wanted to continue to be sexually active, and queer activists who lived communally so they could save money to produce fanzines. A few years before that we’d built a clergy house for the Spanish Catholic Church. They held a competition to transform a building in Plasencia into a residency program for elderly priests. We entered the competition, presented our ideas, and amazingly we won [with Casa Sacerdotal Diocesana, 2004].

These days, it seems, there’s no contradiction in having both Cocky Boys and the Catholic Church as clients.

They’re both about bodies responding to networks and the role architecture plays in that...So we started to do more research about sex in urbanism, which eventually led us to take a look at how Sex and the City revealed it and enacted it, studying how it became a roadmap for developers in Manhattan.

You never said it directly in the exhibition, but I got the sense that your conclusion is that while Sex and the City seemed like enjoyable, harmless fun, it accidently ruined Manhattan.

Sex and the City challenged many of the things that we loved about Manhattan. Manhattan was traditionally a place where minorities would come and become empowered; it was a bubble of emancipation for those who couldn’t find it in other parts of the world. The show always played with many possibilities. It was never fixed. It was an evolution. The transformation of the city was bigger than the characters. They weren’t in full control of what happened to them, but they kept discussing it.

Though as they did so, the city was transforming itself. Your film in the exhibition sums up Manhattan’s current incarnation succinctly as “sanitized, asset-oriented urbanism.”

The four lead characters in the show were part of an ecosystem where many conflicts emerged. Their Manhattan became very segregated. It’s loaded with many forms of exclusion and reductionism, but I don’t look at it as good or bad. We simply examined it for what it is.

You present the show’s influence without demonizing its impact.

I’m glad that was your impression because that was the idea. There is no space for nostalgia here. Many things were, let’s say, born with this show. It created new ways of subversion, new forms of amazing interaction. And this is our space now. It’s a space for us to occupy. My office is trying to bring politics there. Precisely because I consume Grindr and I am, let’s say, a Sex and the City person, [because] it’s my space, my practice is working there. We’re inhabiting it.

I think it’s admirable that you’re not afraid to investigate contemporary popular culture. It’s something architects and academics have typically been scared or embarrassed to work with. We’re taught to feel that it’s frivolous and not worthy of rigorous examination.

I would say it’s super serious. It informs society very directly. Whenever I bring up Sex and the City people tell me super-important things that happened to them related to the show. The things they tell you are extraordinary. Wow!

I forget who said it, but I always remember it: “Give me a new literature, and I’ll give you a new architecture.” It’s funny to think of that with regard to Sex and the City.

Exactly. That’s it, a different literature with a different architecture. Design works like that. We use research to understand the context we’re operating in. But once we understand that, it’s easy to discover that design is at the center of the making of our societies, and the political performance of our societies is very much in the hands of design. It all depends on design.

So where does that leave your Office for Political Innovation?

With many opportunities. We have to create inclusive spaces that are loaded with alternative ideologies and sensitivities. It’s our role to queer up the Sex and the City enactment we’re immersed in. That’s why I’m so excited about architecture. New architecture can make many realities emerge.