AGOSTO MACHADO

Interview by Michael Bullock

Photography By Jack Pierson

Apartamento Issue, 34

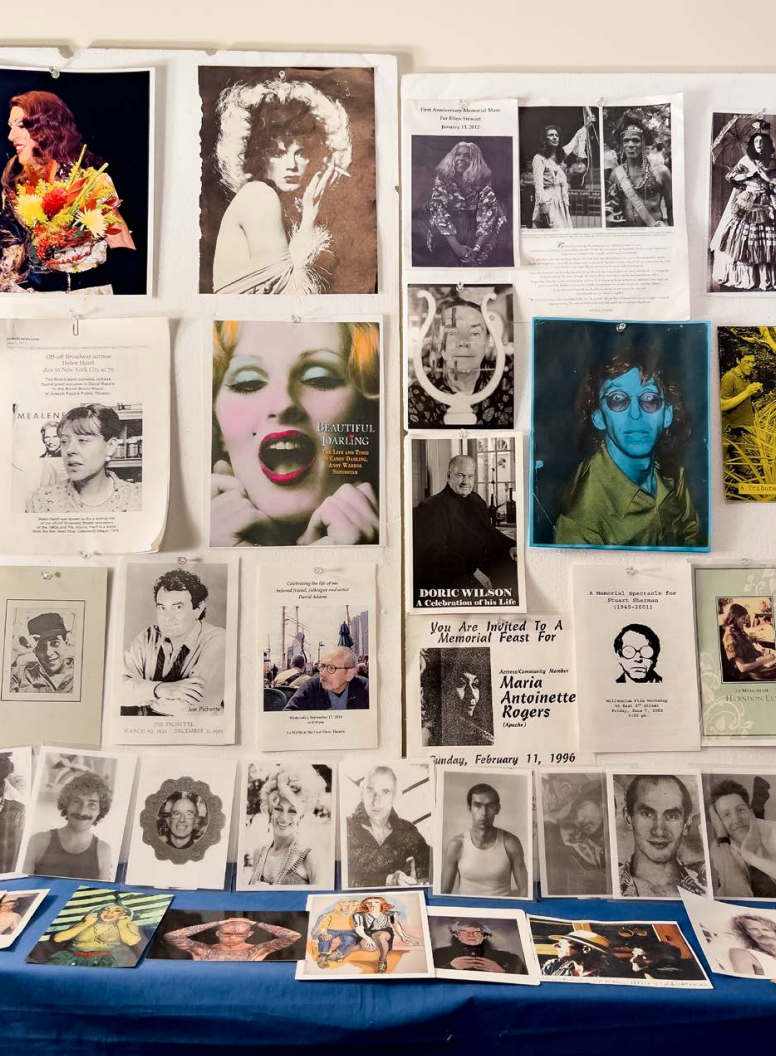

A figure both unassuming and magnetic, artist archivist activist performer Agosto Machado’s transcendent life is a subcultural version of the American Dream. An orphan and former hustler of Chinese, Spanish, and Filipino descent, Machado, through collaboration with his coterie of outcasts and street queens, shaped the counter culture of the ‘60s and ‘70s, forever impacting American art, sexuality, and politics. Machado quit school in the sixth grade, navigating the tumultuous streets of New York City with joyful resilience. His playful charm and openness connected him with an inner circle of now world famous icons, legends such as notorious Warhol superstars Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis, pioneering artists Jack Smith and Peter Hujar, and two key protagonists of the gay liberation movement, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. Thes eclose friendships placed him at the epicentre of many of the most pivotal moments of gay history: the formation of the Gay Activists Alliance, the Stonewall Rebellion, the first Pride marches, and the AIDS crisis. In the 70s, he joined the glitter loving, psychedelic performance troupe, the Cockettes, a collective revered for their wild, gender bending celebration of non-conformity. His career is also defined by his lifelong involvement in the downtown theatre scene. La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, a vital space for avant-garde experimentation, has always been his second home. His performance is marked by improvisation, storytelling, and a deep connection to the communities he represents. Entering Machado’s compact studio, one is enveloped in an overwhelmingly eclectic mix of relics and mementos.

It’s clear that he is not a conventional archivist: he’s transformed a clinical job into poetry. He is the keeper of the flame for the energy, spirit, and beauty of his generation,he is a custodian of moments that would have otherwisefaded into obscurity. Since the ‘60s, he has assembled his collections of artefacts into shrines, appropriating the presentation of religious altars, creating reliquaries articulating his history, politics, and the individuals whose energy and aesthetics secured greater liberation for many.

I was going to start by asking when you first began to make shrines until, on my way in, I saw your shocking sign that reads: ‘MY WILL + TESTAMENT ON FRIG. BELOW’.

Well, it takes months to make one. I’ve been making shrines since the ’60s. All the street people I knew were so nice to me, and they died. My shrines honour them. Regarding my will, I’ve already prepaid my cremation at Redden’s on 14th, across from Our Lady of Guadalupe church. I did that because so many of my friends had to have a collection for a burial or cremation, and this way, I don’t have to bother anybody.

How much does a cremation cost?

I got a discount—$2,000 cash. There’s not going to be a funeral or a ceremony. I will be scattered with Marsha P. Johnson’s ashes. Here’s Marsha.

Those are Marsha P. Johnson’s ashes?!

Some of them. I’ve shared them with many people. Here are some other ashes: Holly Woodlawn and Jack Smith. I think that’s Jack in there. I don’t have my glasses on.

Marsha and I share the same birthday!

She was like a bodhisattva, a holy person walking through the West Village. She always gave people encouragement to be who they wanted to be. She would say, ‘We’re in the Village, we’re free, live’.

When did you move into this apartment?

Oh, I got here at the turn of the century. I had lived on 4th Street for 26 years. I moved therearound 1970. 4th Street, between Bowery and Second Avenue, was not a welcoming block. Ellen Stewart got a grant from the Fords, and so she bought a building on 4th Street and opened her theatre. It became like a second home to me, a place to collaborate with friends. La MaMa is in its 63rd season, internationally known and appreciated.

I don’t see a bed in here.

Well, this is the best place I’ve ever lived. Every outlet works, I get heat, and this is a rehabilitated bathtub in the kitchen. I was

very fortunate. Twenty-six years on 4th Street with an evil landlord who would start fires and scare people out. When I was young on the street, I learnt from older queens who were raised during the Depression. They said, ‘One of the things you learn in life is to do without and make do with what you have’. And so I make do with what I have, and I’m so grateful. Every day I have a safe, clean place to live. My friend Tabboo! is always after me about getting a bed, but I’m comfortable rolling out this mat at night. Check this out—Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn signed these tomato cans.

I’m sure you’ve told the stories of how you met each of these illustrious people a million times, but would you mind sharing how you and Candy Darling met each other? I was told you were a primary source for Cynthia Carr’s recent hit biography, Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar.

As I say, I’m an old street queen from Christopher Street. I met Candy before she was a platinum blonde. She was sitting on a stoop, one that faces Gay Street, right below Green-wich. I started talking to all these people that hung out there, and little by little, I recognised their faces. ‘Girl, what are you up to? Whatare you wearing?’ We street queens had to bevery thrifty. We didn’t dress in high style, but Candy was always so mysterious and beautiful. Even with brown hair, she exuded glamour and mystery. Andy Warhol could take her to Fifth Avenue and Park Avenue gatherings. She’s a lady. She knows which fork to use and how to sit with her knees together. She would mingle, very civilised, and people were charmed. ‘Who is she?’ ‘Well, she came with Andy, so she must be somebody’.

How do you define the term ‘street queen’?

Street queens were mostly homeless kids whowere either thrown out or ran away to New York City and lived by their wits. I was an orphan. I would never judge anyone who sells drugs or their bodies because we’ve all donethat. We weren’t stealing or robbing anybody.

Did you hustle in that period?

Yes, yes. I’d give early commuters in Port Authority and Grand Central Station a good morning blowjob for a couple of dollars. Or when they were going back home to the suburbs in the evening, men would put their attaché bag down right next to their feet, part their overcoat, and I would give them a blowjob for a couple of dollars, then they’re off on the commuter train. What was amazing was—maybe I’m exaggerating—but I remember 30 urinals across, and so many men were jerking off. Or they’d go into a stall and tip the attendant so two people could be in a stall. Today in Grand Central’s bathrooms, there are only a new urinals and a few stalls left, and there’s no hanky-panky.

How old were you when you started?

I started around puberty, but I wasn’t alone.There was a competition. As a teenager, I was prized. I didn’t really have a business sense. Money is money. I could last a long time on $10. The strangest request I ever received was from a man who wanted to shave me. I had peach fuzz until I was about 15. He offered $100 to shave me. I wasn’t scared of his razor. Back then, $100 was several months’ work. I didn’t even have to jerk him off. It just amazed me.

Did he save it?

Yeah. He thought it was a real prize.

Your own youth was also the heyday of NewYork City bathhouses.

An older queen used to bring me to the Everard Baths in Midtown. The steam room was ankle-deep with some fluid. They said, ‘Comeon, girl’. And I said, ‘What?’ And he said,‘That’s Tennessee Williams!’

Oh, fab.

This was way back. And then later, somebody said, ‘Oh, that’s Edward Albee’. But it wasn’t Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee because he hadn’t written it yet. Back then, he was a downtown playwright. It was early, and he still had his anonymity. There used to be sex everywhere all the time. Giuliani closed all that down. A certain set of gay people took umbrage; they felt it was our right to have sex anywhere, any time in New York City. My generation is long gone, but I’m happy to know your generation can use their cell phones and arrange to have sex morning, noon, and night. ‘Oh, I’m on a break now for 15 minutes. Are you available?’ These days,

people can organise sex so quickly and easily.

Around that time, you met some of your closest allies. You obviously had a spirit that connected you with the most avant-garde artists and activists of your generation—people thatwere way ahead of their time.

Well, people who struggled. There’s Sylvia’s determination and that painful struggle of being a part of a gay movement that excluded her because of the garments she wore. Where as Marsha P was so welcoming and so friendly and had a kind word for everyone. Two different personalities. But Sylvia went to the mat for the struggle. I think she was 14 when she was working 42nd Street. At that time, you had to pay off the police. If you were working, you gave them a dollar. A dollar used to buy something. I was never tough, so I worked 46th Street. The movie houses, you know, jerking off old men and things like that.

I find it amazing that you knew each other at such a young age and both started off hustling, and then together, along with Marsha P. Johnson, went on to launch the gay liberation movement. Thank you for starting the fight for our rights.

Well, it happened. I don’t say ‘I’. I say the royal ‘we’. My feeling is, one of the reasons I’m interesting is because I did the journey and I’m still alive. Little me really didn’t make a big, significant difference. Yes, I was part of the Gay Activists Alliance, and yes, I was this and that. But I was just sort of a witness, really. I don’t think of myself as an innovator.

Although you’re a witness that holds the ashes of multiple icons. That’s definitely more than just a witness. Together, you made history.

Well, it was an honour to be friends with them. Even with the downtown crowd, some people wouldn’t acknowledge them. Because they were trans, and also with the fear and ignorance that came with AIDS—I don’t want to start crying, but friends started to get sick before it was called AIDS.

Peter Hujar was one of the people you helped care for while he was passing?

Well, no, I can’t claim that because—how do I diplomatically say this? Not everyone in his protective circle was on board to have me around. How did you find out I was connected with Peter? Because that’s very private. There are people who really don’t want my name connected with that.

Well, he shot those famous images of you, and I also listened to the oral history that you did.

I said that? I’m such a big mouth! In our peer group, in our neighbourhood, there were people who suddenly became invisible. Because they were sick or were suspected to be, people would turn away or walk into a store just to avoid them. The ignorance and fear were mind boggling. Families turned their backs on blood relatives. No funeral, no nothing. Everything they owned was burned because they thought it might carry the disease. I helped people pack up if they had a roommate that passed, and I kept all the mementos. People say I’m an archivist; I call myself a hoarder.

Hoarders keep everything. You only keep treasures. What compels you to keep something?

Instinctually, I want to preserve. I just cannot part with mementos.

After your very first and only solo show as a visual artist, just two years ago, MoMA ac-quired one of your shrines for their collection.

It boggles the mind. That show was of stuff I’ve been doing for decades, honouring all these odd objects that belonged to people. I was so pleased that Gordon Robichaux invited me to show my shrines. Stuart Comer, the curator of media and performance at the MoMA, was given a special tour and somehow selected it. I’m very shy about telling people.

Why? It’s amazing.

Yeah, but there are a few people in my circle who really don’t see it as art. They think it’s too esoteric. They came to my show and said, ‘Why are they showing this shit? Yes, it’s nice you make shrines to honour the dead and kept all these Jack Smith mementos, but what does it all mean?’

I’m happy to explain it to them: It’s a visual and archival creative practice that you have cultivated over decades to honour your community. When you share your shrines, the viewer understands something specific about the history and the individuals whose energy and aesthetics secured liberation and freedom for many. You have collected the relics of gay history. You intuitively understood the importance ofwhat you were living. What does it mean foryou for your shrine to be shared does it mean for you for your shrine to be shared with MoMA’s very large audience?

It’s a very personal thing because all these people are gone. I still feel their kindness and contributions to me—my contribution is to acknowledge their existence.

Despite all the death you’ve experienced, you seem quite joyful.

Because I truly believe that there’s an after life and that our body is just a shell and that all these wonderful people who’ve been so generous to me, I will see them again. I’m acknowledging them for the living.

I just saw you in a New York Times video addressing some of Stonewall’s popular misconceptions. You said—

Oh, dear. Are you sure it was me?

I’m sure. It’s been a popular myth that those riots were partly triggered because of Judy Garland’s death, and you stated, ‘God bless Judy Garland, but no! She was not the cause of the Stonewall Riot’.

I’m starting to have a slippery memory, and I have to be very careful. Some friends who are older have given interviews and later said, ‘Why did I say that?’ I was at the Stonewall Riots. I was outside. The conflict lasted the rest of the week. That’s something people don’t always mention. It was amazing to see so many women, the feminists and lesbians. They were just as vulnerable because when the police started swinging, they beat on anybody in their way. We were demonstrating for our rights, and the police were allegedly paid to beat us.

As someone who was originally there, how do you feel about how we’re doing today and what Pride has become?

At one of the more recent Pride marches, there were effigies of Marsha. My friend Kenny Angel Davis was handing out portraits of her to all these young kids, but they didn’t know who she was, and they just threw her image away. I don’t expect young people to know who is who. It takes time. Just like I was ignorant of so many things when I was young.

In that period, did you realise that Stonewall would become the turning point of the gay liberation movement?

I had no idea. All I knew was we were fighting for our rights. It’s only due to the media that Stonewall made international news. If we look at history, there was a similar protest in San Francisco and also in LA, but those didn’t capture the imagination. New York City being New York City, it had the largest number of very supportive LGBTQ+ people downtown and their allies, and Stonewall Riots is a catchy name.

Are you happy that Marsha and Sylvia are finally getting the acknowledgment they deserve? They’re almost approaching sainthood.

Yes, very much so.

Did you see that coming?

No. After one of the first few Pride marches in the early ‘70s, the crowd gathered at Washington Square Park. Sylvia had to fight her way onto the stage. She told the audience if it wasn’t for the drag queens, there would be no gay liberation movement; we’re the frontliners. She was booed off the stage. I was shocked.

You witnessed that famous speech in person?

Yes. I was just be wildered that she fought so much and so early and that they weren’t going to let her talk. She had to fight for support within her own community.

It’s amazing that this moment is captured on film.

It’s part of history.

You’ve talked a lot about the past, but your current life is also impressive. Your close friends are a vibrant family of artists: Jack Pierson, Tabboo!, Anne Hanavan, Jimmy Paul. And your own work continues to develop with support and growing interest.

I keep busy. I’m fortunate. It amazes me that there’s curiosity and interest. I don’t have alot of interaction with the new generation,but I’m so happy and amazed by these young people in their 20s and 30s. They have to make a lot of money to be in New York City. It’s not just poor and working class people who have to have three roommates. It’s like, yes, life is expensive, but they still choose to live in the East Village. It’s still a place where they can affirm their art or expression. I love their energies. Like these outdoor restaurants. We used to have have sex al fresco; why not eat al fresco?

We haven’t talked much about your love life.

Honestly, I’ve had wonderful, very dear friendships, but the nature of my journey is that I really haven’t ever had a long term relationship.

Why do you think that is?

I’m a private, shy, introverted kind of person.

Hold on, weren’t you a Cockette? How could a member of one of the most groundbreaking, flamboyant, queer performance troupes be a shy, introverted person? My impression of you is completely the opposite.

I live a quiet life. I go to some art openings, but other than that, I see only a few people. I see myself as a private person who happened to engage specific people at a certain time and place. At this late stage of my life, I still cannot sing, dance, or

act, but I can babble. And that’s one of the things I do—just tell stories with no particular rhyme or reason.

So you’ve been a performer your whole life without any of the typical skill set?

Some people say, ‘You’re an actor’. No, no, no! I perform. I don’t act or sing or dance. And if you’ve ever seen me on stage, you know that’s true.

But you love performing?

When it’s with friends and it’s collective. I like when people who know my little faults write parts specifically for me.

Over six decades, you have acted in almost 80 performances. What are you most proud of? What was most important to you?

Well, a highlight was carrying the gay activist banner up to the park during the first gay pride parade. There’s a photograph to prove it, thank God. They call it a march, but it wasreally more like a run because the anti-gay people threw eggs and tomatoes at us, so we had to move quickly. Once we got to the park, we knew we survived. I think that was a very important public statement for our community. Being part of that was so meaningful.

I didn’t know about that, that’s beautiful. What has been your favourite period of New York City?

As much as I enjoy walking down memory lane, I like to be where we are, in the now. I cherish the past and speak lovingly and warmly about it. We did it together, and we’re here now.

Emotionally, what is it like for you to live in an apartment with the ghosts of so many of your loved ones?

That’s a good question because I think allthese people are still giving me energy, light,and confidence—their lives, their friendship, and wonderful memories. Some friends think I’m living in the past, but I’m not. I’m experiencing a reflection of what was and what continues until we meet again.