WALTER PFEIFFER

Text by Michael Bullock

Photography by Walter Pfeiffer

Aperture 235, 2019

Orlando, the fictional main character of Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel and Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation, starts life in the Elizabethan era as a failed male poet. But by the story’s end, because of a magical pact and an unexplainable act of gender transformation, Orlando finds themself living well into the present day—1928 in the book and, 1992 in the film, which ends with Orlando just beginning to find success as a female novelist.

Though it didn’t take centuries for Walter Pfeiffer to find commercial success, it did take decades. Pfeiffer happily defines himself as a late bloomer. “It’s only because I never gave up,” he says. “I was never pushing my career. I just had to do the work for myself. I’ll work until I can’t anymore.” And so, it wasn’t until the early years of the twenty-first century, when he was in his fifties, that accolades and international recognition finally found him.

But while there is a parallel between the long artistic trajectory of Orlando and Pfeiffer’s own, Pfeiffer’s work is more linked conceptually to the supporting character, Queen Elizabeth, portrayed in the film delightfully by queer-icon Quentin Crisp. (“I love Quentin Crisp,” Pfeiffer says.) The dying queen’s obsession with Orlando’s haunting beauty leads her to strike up an unusual deal. In the film version, on her deathbed, she offers the stunning boy land, a castle, and unlimited wealth. In return, she instructs Orlando, "Do not fade. Do not wither. Do not grow old.” The old queen uses her wealth and power to preserve youthful male refinement.

Pfeiffer shares the same objective, but carries it out with a much more obsessive, hands-on approach. Since the 1970s, he has stopped hundreds of young men from aging, freezing them in time with his camera. “My models are at the height of their beauty,” he says. “I might see them just three or four years later in the supermarket and I barely recognize them. They are married. Some might still be nice but most of them—you wouldn’t believe it—whatever they had is gone.”

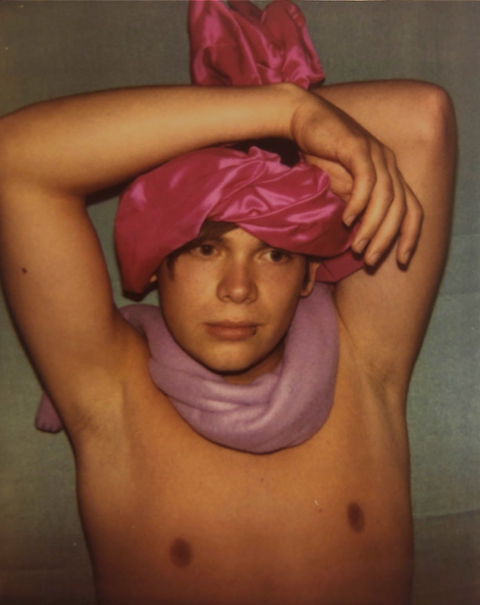

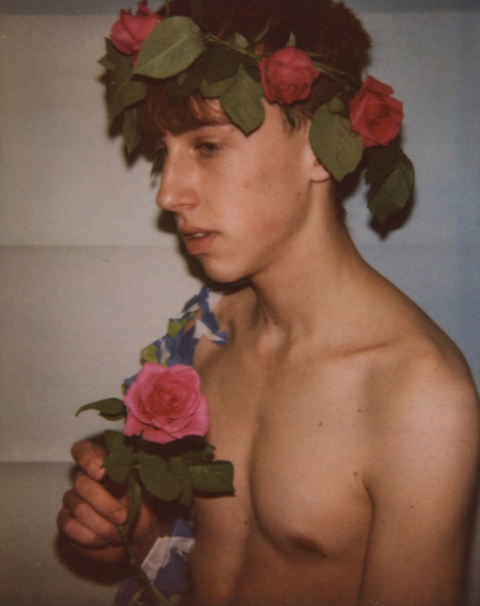

His subjects are typically in their late teens to mid-twenties, the period of life that speaks to another central theme of the book and film: gender fluidity and transformation. During his photoshoots Pfeiffer never discusses issues of masculinity and femininity with his models; each pose and prop he suggests are simply a collaborative experiment with the goal of making an image “that works.”

In some cases, this allows typically macho boys to reveal their softer sides.

At the start of this project a very feminine art school boy approached Pfeiffer, volunteering to model and although the student was not the type he is typically drawn to, he accepted thinking he might be a good match for the theme of Orlando. In the end the model fell thorough and Walter was happy it did. “It would have not have been boring to duplicate the film literally, I could have photographed a boy with lipstick but it would have been obvious, it just didn't work this time.”

In the end Pfeiffer turned to his Polaroid archive and chose images in relationship to the film instinctively. The pictures in this portfolio span the length of Pfeiffer’s career from black-and-white images taken in the 1970s up until the opening image of the flowers and the hand (TITLE) taken in 2013. The photographs of boys wearing silks and flowers (TITLES) have an obvious affinity with the visual language of the film, yet one stands out as a curious outlier—the YEAR image, TITLE, of two masculine boys with matching Virgin Mary tattoos. As Pfeiffer explains, “I had never seen boys with the same large religious tattoo. It was unbelievable, so I had to take a photograph of it.” But in his own indirect way, this image gets to the heart of the matter, a literal and humorous illustration of gender symmetry.