UNITY SKATEBOARDS

Interview by Michael Bullock

Photography by Daniel Trese

GAYLETTER 9, 2018

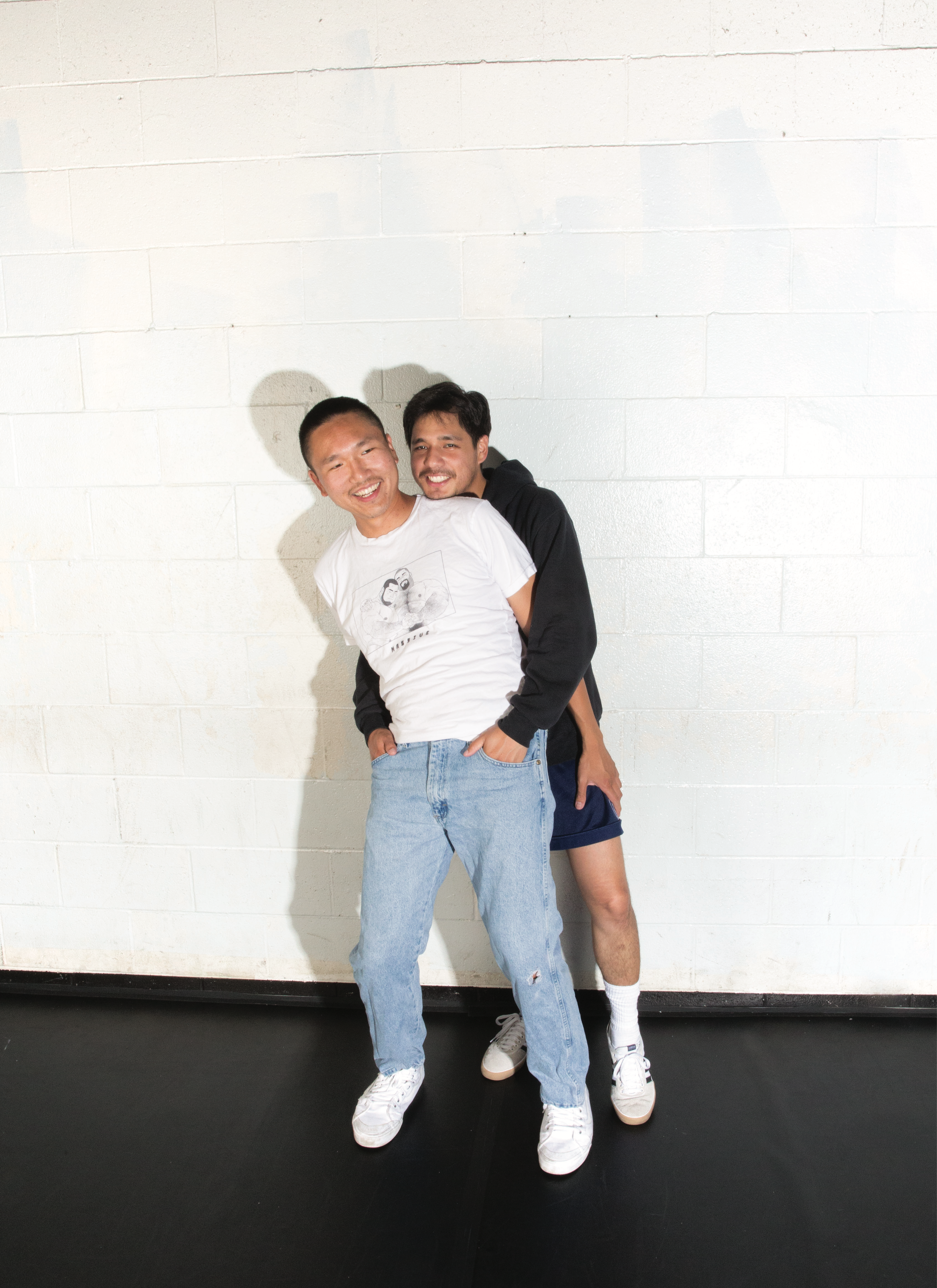

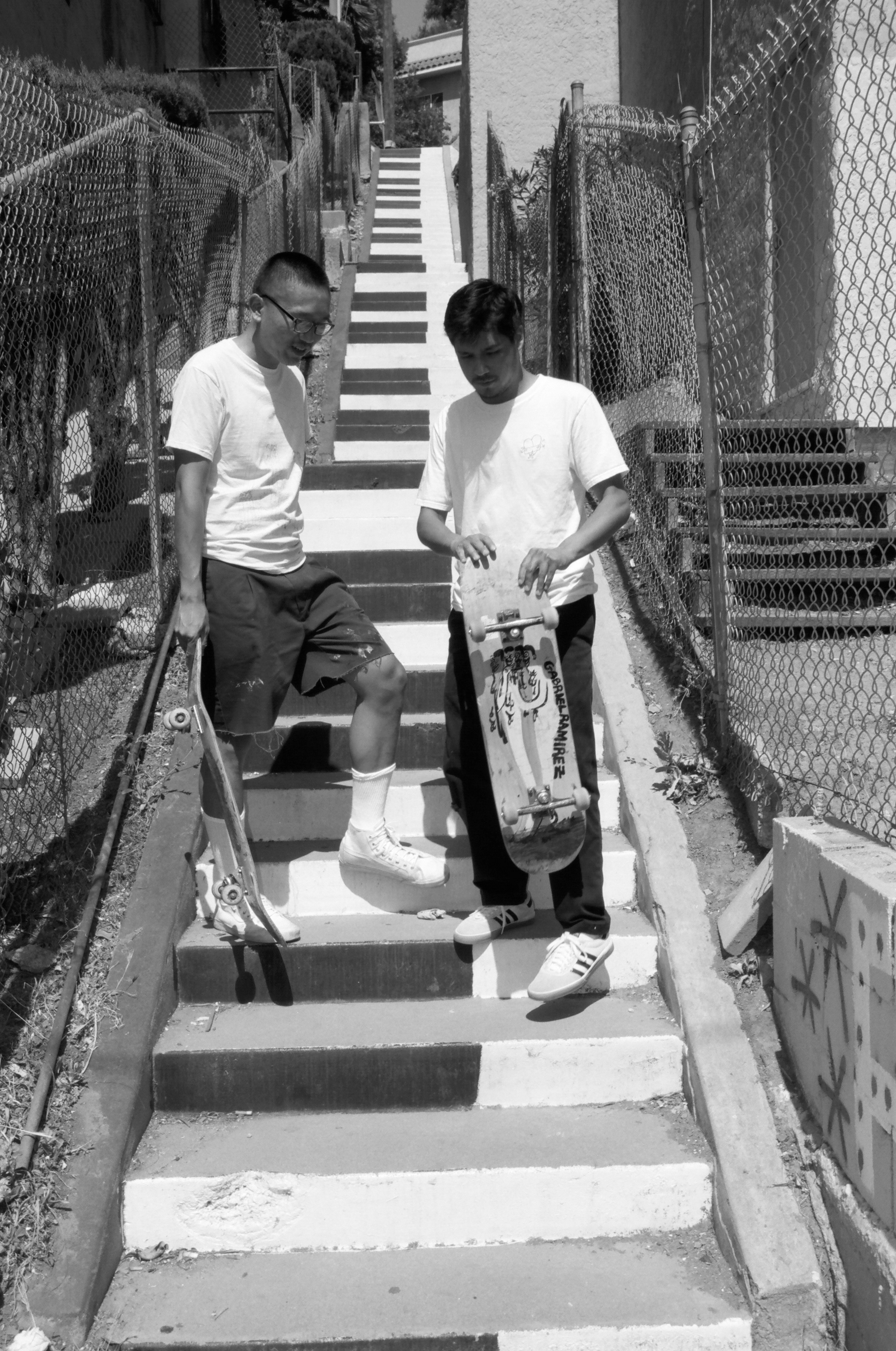

Ironically, America’s disgraceful 45th president can be indirectly credited for a handful of substantial developments in patriarchal dismemberment: mainly, the #METOO movement and the election of Danica Roem (the first transgender women to win public office in the United States) but the most unique act of reactionary activism has been the arrival of over a thousand pink skateboard decks distributed throughout American cities and beyond. Chinese-American artist Jeffery Cheung’s hand painted boards showcase imagery that until recently was unthinkable in the macho, predominately white, homophobic world of skating. His cartoons depict chubby, naked, same-sex, mixed-race couples embracing with joyful smiles. Each board is branded UNITY and paired with empowering slogans such as: “Don’t be Afraid of Who You Are,” “Queer Skateboarding: Like it or Not,” or “Together as One.” These decks are tools of defiance. Using one empowers its owner to be a fearless queer skater, and that visibility encourages closeted skaters to also participate. I sat down with Jeffery and his boyfriend and key collaborator Gabriel Ramirez in their downtown Oakland headquarters, a lofted studio above Wolfman Books. The humble, almost reluctant leaders of the new movement explain how in just over a year they managed to unite queer skaters worldwide and what their vision is for the future of UNITY.

Were you a closeted teen skater?

Skating is all I did in middle school and high school. I knew I was gay early on, but I never felt comfortable enough to come out because, when I was skateboarding, I heard other skaters use homophobic slurs — things like “faggot” or “that’s so gay” — all the time. I came out right after high school, and I stopped skating about the same time, when I was 19. I started again when I was 27.

Why did you start again?

I met Stevie Shakes and Cher Straub through music, and we discovered we had all been teenage skaters, so we got back into it together. It blew my mind that other queer skaters existed. I had never met any before. This was around the same time that [professional skateboarder] Brian Anderson came out.

Were you surprised to have a sponsored pro skater be so open about their sexuality?

No. There were rumors, but I was so happy when he officially came out. It made things a little easier for every closeted skater.

Did that encourage you to start Unity?

I never thought, I want to start a company. I was mostly inspired by Stevie and Cher because they were the first queer people I skated with. On New Year’s Eve 2017, I sent them a drunken text that said something like, “Let’s order some boards and paint them.” It turned out we already knew a few other queer people who were into skating, and the circle was already bigger than it seemed. And it just kept growing.

Was Unity always the name?

I’ve been using Unity for everything: our band, our zines. It had been around for five years, but it made the most sense with skateboarding since our goal is to encourage queer people and queer people of color to skate.

Were you an artist before you started painting boards?

Yeah, zines came first. I still make them all the time. I took a queer printmaking class after high school and studied painting and printmaking in college. My work has always been about sexuality.

What did you paint on the first board?

It probably looked like this [Jeffrey points to a board featuring a chubby, smiling, bearded naked man, lifting up his legs, proudly showing off his cock and ass] but shittier.

So you, Stevie and Cher started using the boards, and friends started asking for them?

It was strange how fast it picked up. Because of Brian Anderson, queer skating was a very hot topic. I posted something online a month after having the idea, and we got a message from a journalist at i-D magazine wanting to cover Unity. It wasn’t even anything yet. At its start, skateboarding was a counterculture activity for surfers, misfits and outlaws. It was an alternative to jock culture. Its values started off as DIY, punk, anti-mainstream — except when it came to sexuality. Skaters, generally, have always been unaccepting of gay people.

I think it hurts even more than not being accepted in football or baseball, because skating was a space created for outsiders, but then those outsiders rejected queer people.

Skateboarding doesn’t require the infrastructure of a team sport: You can just pick up a board and go skating. But even though it’s an independent activity, the culture around it became really macho. When skateboard culture was beginning, it was for weirdos and outsiders, but skateboard culture today is pretty mainstream. In a way, Unity is taking a step back to skateboarding’s roots, when people embraced being different and going against conventions.

When I was at the launch of your new headquarters, I heard you say you painted your thousandth board.

I’m somewhere around a thousand or passing a thousand. It happened pretty fast. We just got this zine today from one of the first people who reached out to us after the i-D article. They’re a queer skater from Malmö, Sweden, and they make a zine about genderqueer skaters. We have an ad in it. There’s never been a platform for queer skaters to get together or have any visibility. We quickly found out after we started that everyone was already there. Together we’re breaking down stereotypes about what a skateboarder looks like or who’s allowed to skate. I think it has really also been about timing. This pushed us to take action and do something positive in response. It was clear, more than ever, that we needed to support ourselves and our communities. This was our way of healing in the face of the threat posed by the new system. It was a way for me to take action.

When was the first time you made an open invite for anyone to come skate with you?

We call them Queer Skate Days. The first one we did was in July 2017, then we started doing them monthly. We already had a group of people we skated with regularly; sometimes it would grow, but it was mostly the same people. We got messages from people in the area saying, “I’m queer and I wanna skate with you.” So I made a flier that said where and when we’d be skating, and I invited anyone to join. It was a huge turnout — skaters of all ability levels came out. It was so amazing to see all these queer people skate together. What we learned is that a lot of people don’t skate or stopped skating because of how hostile the skateboarding community can be to non-straight guys. We’re creating a space for people to learn, feel safe and have fun.

Do teenagers attend?

Yeah, actually! Another motivation for me is thinking about how much this would have affected me if it existed when I was younger. It would have made a huge impact on how I saw myself. I would have felt better about who I was, and I wouldn’t have thought I was alone. Maybe I would have kept skating. I love skateboarding. It can be such an empowering sport, so it’s too bad that the culture around it can be so shitty. I believe that’s reflective of society at large. It’s so much easier for boys, even gay boys, to participate. You’re more easily accepted if you’re a masculine-presenting person.

Is that why you use always say Unity is queer instead of gay?

I didn’t want it to be just gay boys skating. That would be too similar to what skate culture already is.

Parts of gay culture can be just as misogynistic as straight culture.

Yeah, totally. That exists in the gay male community, where there’s tons of racism and shitty politics. We didn’t even think about it too much. We just wanted to invite everyone who was shunned from skateboarding, including genderqueer, nonbinary skaters. Tons of gay boys are accepted in skating if they remain closeted. That was the one place in high school where I felt accepted, but I realize that is the privilege I had as a masculine-presenting person. This project has made me understand what many of my peers are going through. A trans kid wouldn’t get the same amount of acceptance I did. [Gabriel Ramirez, Jeffrey’s boyfriend and collaborator, joins the conversation.]

How did the skateboard giveaway for kids under 21 come about?

Jeffery Cheung: I’m fixated on how having something like Unity would have changed my life when I was younger, so I started brainstorming about how we could directly reach out to queer youth. Then we came up with this idea for the giveaway. We posted fliers around the high school nearby, and so many kids came. I painted 52 skateboards that day for queer kids under 21.

Gabriel Ramirez: We bought all this Lacroix and got pizza donated. A lot of kids were freshmen in college. JC: A lot came from San Francisco. A father drove his 15-year-old son from Sacramento, two hours away. GR: It was so sweet. I almost cried.

JC: The amount of kids that came was really surprising. One kid told me his therapist told him about the event. Somehow word just got passed along. Social workers saw the giveaway as a rare opportunity for gay kids to meet each other and not feel so lonely. As I painted boards for them, I’d ask, “What do you want the character to look like,” and they would say, “Oh, I want them to be genderless.” There were a lot of genderqueer, genderfluid kids who were really young. When I was that age, kids didn’t understand themselves in those ways. It’s a simple but radical gesture. Unity must be a dream come true for queer teens. When you’re too young for clubs or bars, your main point of entry into gay life is often through sex apps, which can sometimes make you feel even more isolated. It’s a breakthrough for kids to be able to come together in a group activity where friendships can form and they can build a community.

GR: That day was amazing. The kids took over the whole complex, and they were so happy to meet each other. I remember walking around, just checking things out, and I overheard conversations like, “I’m a senior at such-and-such high school, what high school do you go to?” It’s rare for queer kids to have the space to connect as peers and for them to be able to learn what they have in common. They are usually afraid to open about who they are, but that day, everyone was so comfortable. It was adorable.

Did it launch many new skateboarding romances?

JC: Kind of! Mae and Cher met through Unity. Mae is 20 years old. She’s a trans girl from Bakersfield, the homophobic, transphobic outer, outer suburb. She saw a sticker of ours and she found us online and came to meet us. I gave her a board, and she met our friend Cher and they just hit it off immediately. Now they’re the cutest couple in the world and they skate together.

GR: That’s her right there in the middle in the New York Times article. The one jumping in midair.

JC: That was really cute to see, but the best part is there are so many groups forming. We’re not the only queer skate collective: Pave the Way Skateboards, they’re another one. They’re based in L.A. and Berkeley, and they started around the same time we started. We’re gonna collaborate with them. After the initial write-up in i-D, I would send boards to anyone that messaged me. We sent boards to New York, L.A., Sweden, Canada and London.

GR: Expensive shipping, but it’s worth it. JC: These people were so stoked to get boards. They eventually started meetups wherever they live and they’ve begun growing their own communities. New York now has queer skate meetups, which are going really well.

One thing I’m curious about is that skateboarders are typically young and fit, but the Unity characters you paint are chubby and look middle aged. No one you paint looks like a typical skater.

JC: I don’t want anyone to feel shame about who they are. It’s body positive imagery. I don’t want anyone to feel shame about who they are.

Because you’re not drawing your version of perfection, is your art a conscious strategy to communicate inclusivity?

JC: These were characters I was drawing before I started painting the boards. I didn’t really think about it that much.

It’s refreshing that your drawing style is far away from the slick aesthetics of both gay culture and contemporary skateboard culture. Your work reminds me most of two ’70s artists: Saul Steinberg and Shel Silverstein.

People say Shel Silverstein. Quentin Blake is another one.

GR: And Roald Dahl

JC: I love all that stuff. Growing up, I read Shel Silverstein and Roald Dahl books, but right now my friends and the folks in my community are my biggest influences. All the younger people and nontraditional artists we have met through the meetups and zine-making workshops — those are the people that inspire me. But right now my friends are my biggest inspiration.

How racy do the illustrations get? Do any of the boards ever depict sex acts?

JC: No. Not really. Some of the guys are showing off their assholes. I was into doing that for a while.

GR: Jeff made a banner with that character at one of the skate days and this older woman walking her dog yelled at us and tore it down.

Have there been any other negative or homophobic reactions?

JC: Surprisingly, online, on our Instagram account, we haven’t really received any. Maybe two or three. No one really posts negative comments.

Do you get hit up for dates?

GR: The people that we showcase on our Instagram, like Mae and Cher, get hit up. They’re sort of mini-celebrities. They have fans ’cause of their skate style.

Unity is growing very organically. What do you see next? Where are you going to take it?

JC: The most important thing is to inspire people to build their own communities, to be empowered and to not feel alone. But it’s strange because all of a sudden we’re getting requests from people in the skateboard industry and I’m not sure what their motives are.

The one quality most brands don’t have access to is authenticity. When they know something is authentic, they want a piece of it. It sounds like you have a strong safety net of friends to bounce ideas off of who will keep you from getting exploited.

JC: Whenever something new comes up, we always talk to each other and Gabriel gives me his feedback. I’m really cautious and sometimes paranoid, even with certain news outlets that wanna cover us. We’re cautious about trying to make sure we’re represented accurately. These are all new issues that we don’t have experience navigating, so we get a lot of input from our community. That’s a big part of how we make all our decisions.

As a former closeted skater, I’m incredibly grateful for all the work you both have done to create this unbelievable cultural shift.

JC: It all happened fast. We eventually might pursue it in more traditional ways so we can quit our day jobs and dedicate our full attention to Unity, but for now I really want to keep it going as is. I want to skate more, meet more people, make more boards, encourage and promote whatever queer projects are happening, and support and empower as many queer skaters as we can.