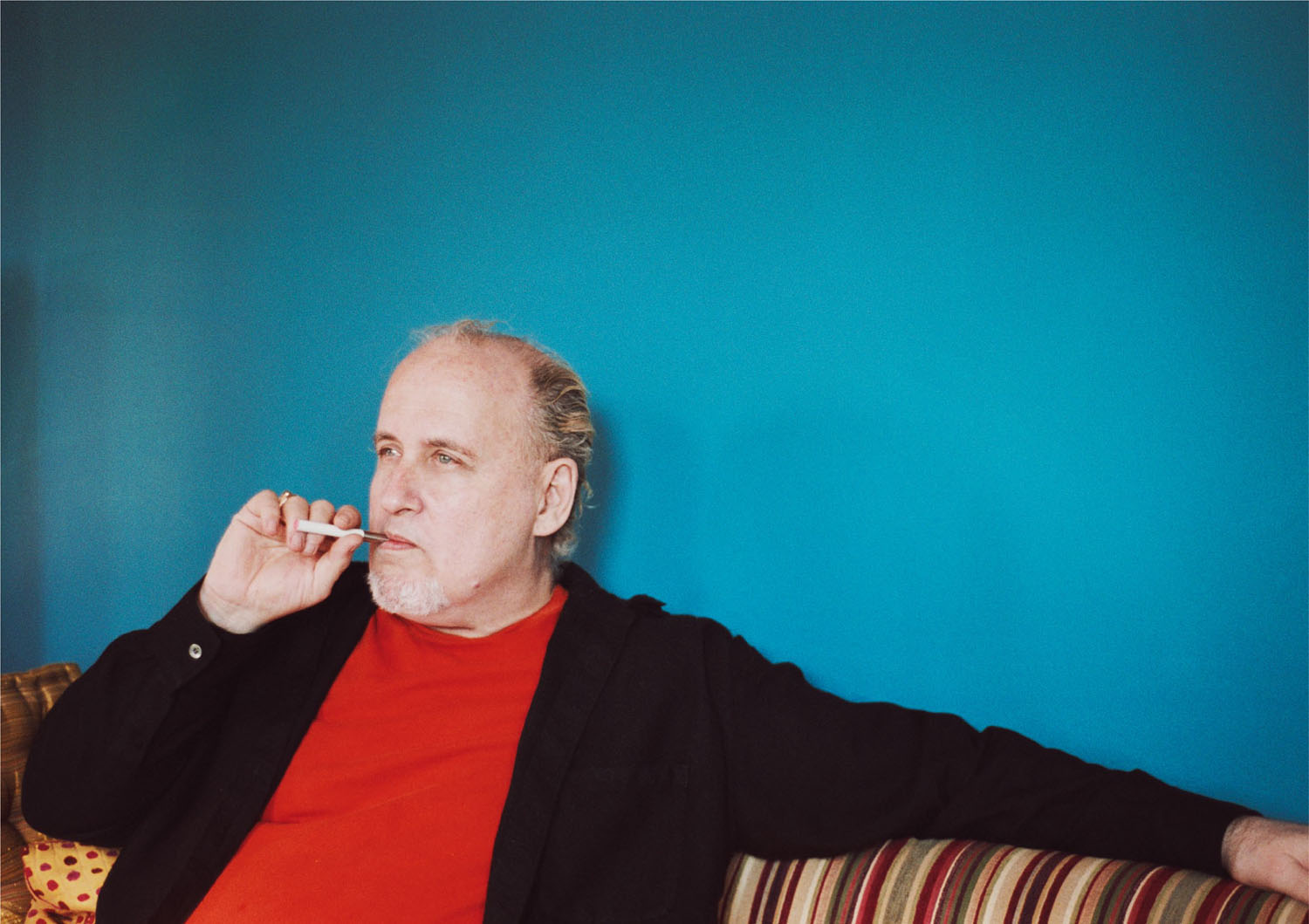

BRUCE BENDERSON

Interview by Michael Bullock

Photography by Thomas Dozol

Apartamento 7, 2011

Writer Bruce Benderson is puffing away on an e-cigarette, his new favourite accessory. He’s just proudly made me what he considers to be scientifically the perfect cup of coffee with a new press he recently acquired. Coffee is followed by many bottles of Prosecco. Bruce is a great host. He hosts like he writes: he’s generous, extremely entertaining, scandalous and sometimes challenging. He’s an aesthete, a dandy and the pinnacle of intellectual refinement, all in the package of a street thug. Bruce learned the ways of the street from spending a good portion of his young adult life hanging out, befriending and falling in love with the hustlers, junkies and criminals of Times Square at a time many consider its glory days. Bruce is famous for bringing these lost worlds to life in his early novels User and Pretending to Say No. His extensive body of work includes other well known titles such as Sex and Isolation, Pacific Agony, and The Romanian: Story of an Obsession, for which he became the only American to win France’s highest literary award, the Prix de Flore. Along the way he was also a leading writer for our favourite magazine of all time, Nest, a publication known equally for its eccentric interiors and radical design. For Nest Bruce profiled such amazing homes as John Waters’ Baltimore Italianate villa, and the Parisian apartment of the Blue Angel of Marmont, the owner of France’s legendary transgender performance venue Club Michou. Through Nest Bruce became well acquainted with fantasy interiors. He’s owned his East Village apartment since 1994, and last year he finally decided it was time to transform it into his own Technicolor fantasy.

Michael, you have a lovely nose.

(Laughs) Thanks.

Have you had surgery? I would kill for that nose. So what do you want to know?

I read in an interview that you once moved a junky friend from Times Square in to your house to help him recover, then another moved in and eventually you had to leave because the whole house was full of junkies. I can’t image that happening here?

It was still happening here at the beginning. I was in love with a murderer who lived here from time to time. I shouldn’t say murderer. I don’t know if he actually killed anyone, but he put two people in critical condition. He’d get friendly with someone, start to respect them and then stab them. It happened three times.

You let him stay here?

Yeah, he stayed overnight sometimes, I mean, I was in love with him. He wasn’t psychotic, like kill you in your sleep type of thing. You’d have to be relating to him and something would upset him. It was off and on for years. The last time I saw him he wasn’t well. He had HIV and started to get so angry about it. We were in the kitchen and he was looking at a knife saying, ‘It’s not you, I’m not mad at you’. I thought ‘Oh god it’s really going to happen’, so I said ‘Let’s go out and get something to eat’. We went downstairs. He went out the door ahead of me and I slammed it shut. We talked several times on the phone after that. He wanted to be a writer because of me. We wrote a story together and it was really good - he had talent. I don’t know where he is now or if he’s still alive. I’ll show you the video of him.

I’d love to see it. I feel strange asking about interior design after that.

Don’t. Maybe what you want to know first is why a writer should be so interested in design and visual things. In my experience it’s incredible, most writers, serious writers, have no eye for anything. They understand ideas and they understand language, but they don’t understand design. I think they repress it. They cut it out. They can go to a museum and talk about a beautiful painting, but somehow design is beneath them. Their ideas are too lofty to be concerned with such things. I believe that artists - and writers are artists - should concern themselves with aesthetics in every area of life: the eye, the ear, the nose. They should be interested in perfume; they should be interested in design, in music. Artists should be like that, but very few are.

Some people are fantastic writers, but they don’t react to colour or form. You can see it in their work. They’re not visual writers. I’m a very visual writer. I like creating a three dimensional visual experience in my writing, I think it’s partly that they lack a faculty for these things, but the other part is that they’re snobby about it. They’ve decided it isn’t important. Some intellectuals decided ‘That’s superficial, so I mustn’t have a reaction to it’. It’s like a woman who won’t react to a man’s looks because... ‘I react to a man who’s wise and kind’. Obviously somewhere inside her brain cells are reacting to bulges and muscles and all that. But she’s blotted it out because she feels it’s wrong in some way.

Like your essay Fear of Fashion where you make a strong case that it’s actually superficial not to judge people by their clothes.

Clothes are a very detailed expression of what’s inside you, to quote my mentor, writer Ursule Molinaro, who’s no longer living. She was a French novelist. She said, ‘Why speak ill of the surface when only the void has none?’ (Laughs)

Well then, let’s speak of the surfaces in here. Why did you decide to renovate?

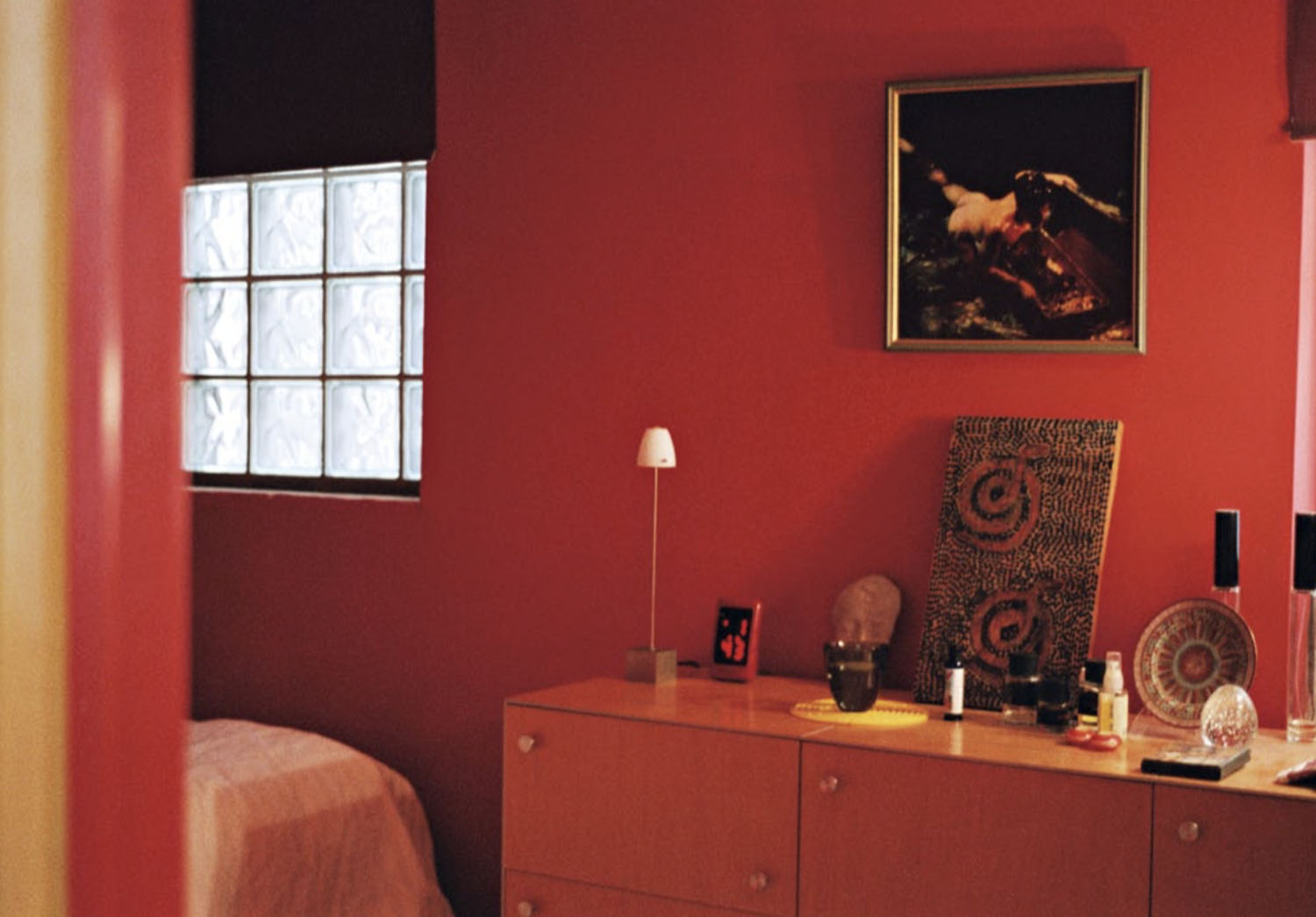

Friends pushed me to renovate, so I got very rebellious. ‘Oh, you’d like a nice fresh coat of white paint and maybe a nice wooden floor, and then you’ll be happy’. I thought, ‘If I’m going to renovate I’ll do something absolutely stupendous’. I started watching old Hollywood Technicolor films and decided I’d create a Technicolor apartment with rooms that had the most saturated colours anyone had anywhere. I focused on two movies in particular. One was The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T, which is a Technicolor fantasy film based on a Dr. Seuss book. The other one was a Rita Hayworth film. I can’t think of the name but it was a musical that took place in London. That one interested me especially, because I noticed the British seemed to have a different attitude to colour than Americans. All my friends say, ‘This room doesn’t get much light so you’ve got to brighten it up by painting it a light colour ’. They also believe in a colour that’s ‘pleasant’ and doesn’t ask too much of you. But all the interiors in the movie were very saturated colours, so saturated that they made shadows in the corner. And instead of making the rooms look cramped it actually made them look bigger because you couldn’t see where the room ended. It was lost in shadow. That’s what I went for.

But then the kitchen is lime green?

Chartreuse with pale yellow cabinets. I love it. I made a lot of perverse choices. I doir knobs for the kitchen cabinets. They’re the kind of glass knobs you’d use on a bedroom dresser and I use them for my kitchen cabinets. I wanted a bejewelled fantasy feel.

Were you pausing the films and trying to match colour swatches – like, ‘this room should be the colour of Rita Hayworth’s dress’.

Did it get that specific?

A little bit. The blue in the living room comes from The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. That’s a highly designed film beautifully pulled together. The red in my bedroom I did because I’ve always hated red. I thought a red room would be really annoying and I wanted to go against that feeling.

Doesn’t red make you aggressive?

No. That particular red, which is a persimmon, an orange red, which I would have thought would be the most annoying red of all, is the most soothing red for some reason. Once I had that red in the bedroom, I decided it was ecclesiastical and chose a purple for the adjoining bathroom. Those are the Pope’s colours, purple and red. That’s what makes it decadent: the Pope’s colours.

That works nicely with some of the other religious icons in the house.

Are you referring to that frieze? It’s my favourite station of the cross, called ‘Jesus is stripped of his garments’. (laughs) It came from a church in the Bronx before it was demolished and is actually just plaster of Paris. It’s not even heavy to lift.

How did you get it?

It was being sold in a junk shop after the church was demolished. I got it for very little money.

And you’re not religious?

No, but I adore Catholic iconography. I simply adore it. I find it aesthetic and also perverse because it’s so sadomasochistic. There’s a lot of nudity, suffering and guilt. The entire history of western art is entirely dependent on the Catholic Church. We wouldn’t even have western art if it weren’t for the Catholic Church. And darling, that’s why I was so attracted to the confessional...

You mean that red curtain?

Isn’t that what you call that velvet structure? That’s what I call it. It’s essentially a black metal box covered in black velvet with red velvet curtains. I got it in the ‘90s. It was supposed to be an inexpensive, groovy closet. But what I liked about it was it looked so much like a confessional. Even more so with the station of the cross next to it.

And the photograph of the nude young man praying?

You may call it praying. (laughs) You really do have a lovely nose; you should keep that in the interview. What else do you want to know?

I thought it would be interesting to know what you think of the term ‘hipster’ today. Your famous essay Towards the New Degeneracy is one of the only literary analyses of the hipster since Norman Mailer brought the term to the mainstream with The White Negro in the ‘50s.

Well, now it’s absolutely meaningless. All it means now is people of a certain age who go out to clubs, people who have a nightlife, and people who buy a lot of things. It was almost the polar opposite when the word first came out. It came out of the expression, ‘I’m hip man,’ meaning you understood black jazz culture. You were completely outside the mainstream. It meant you were alienated, it meant you were non-materialistic, and it meant you hated popular things. What’s the difference between a hipster and a yuppie? It’s just another word for the new generation of yuppies. Weren’t yuppies hipsters? They’re ‘young urban professionals’, that’s what YUP stands for.

Well, yuppies achieved status through being rich and buying luxury consumer goods. In this current incarnation, to be cool you also have to be on top of what’s happening culturally. For the most part hipsters consume culture, and having access to cultural stars is status. It’s changed.

But yuppies were supposed to have access too, you know, to people who would make them rich and powerful in business. You’re right, there’s been a shift. The focus is more on culture than on earning I guess. But it’s just as materialistic, it’s just as consumer-oriented.

In the original incarnation would you have considered yourself a hipster?

Yeah. The big inspiration for me when I was about 12 was the Beatniks. I’d see them occasionally in Life magazine. I was mad for them. I read all Norman Mailer’s books when I was 13 and I read Allen Ginsburg’s poem Howl. That was and still is my idea of a hipster. Hipster came from being hip and what did hip mean? It meant in the know, and it still means in the know. In the beginning it meant in the know about how to avoid the pitfalls of bourgeois life. In the know about how not to end up on Madison Avenue or on a career track. In the know about relating to black ghetto people and being accepted by them. In the know about understanding drug lingo so you could get high and know people who got high too. In the know meant knowing how to avoid the cops. That’s what hipster meant back then.

So, nowadays hipster still means in the know, but what you know about has changed.

Now you’re in the know about the restaurant everyone read about in New York magazine, or a band that’s hot at the moment. An ’indie’ band, it would have to be I guess. In the know now would be to know about fashion. Originally the whole idea was that you were anti-fashion. You wore a pair of black leotards and a sweater if you were a woman, and you wore jeans if you were a man. That was it. You let your beard grow out. So we have two ‘in-the-knows’. One is how to avoid the pitfalls of middle-class life, and the other, new ‘in-the- know’ is how to live middle-class life to the fullest. (laughs) Right?

True. The goal is to have the veneer of cool while remaining very comfortable. Nothing is on the line socially, politically, financially or creatively.

I don’t think there’s much veneer left. When I go out and see the kind of people haunting the East Village I see girls in heels, I see men who didn’t bother to change from the office. They’re not very hip, to me they look like fraternity people. And they’re still calling themselves hipsters. Now a law student can be a hipster. That’s really laughable you know?

Do you think the concept of bohemia is still relevant? In New York there’ll always be a creative community that’s distinct, that supports each other, but I don’t think anyone would sum it up in terms of bohemia anymore?

No, I wouldn’t either, but I think bohemia does exist. It exists outside the great urban centres. It exists in small pockets all over this country and all over Europe. It’s small communities of alienated people who are still excited by disruptive activities and outsider culture. It does exist, but what we’ve learned is that any kind of avant- garde, bohemian production that’s too close to the media can’t keep its authenticity very long. It’s probably happening in Detroit where the city is run down. One thing about bohemia: it has to be cheap. You have to be able to live cheaply, you mustn’t work much to be bohemian, and that’s still possible in the non-major urban centres of America. There are pockets of it all over the place. Just not here, because it’s too expensive in New York. And aside from being too expensive, it’s too ‘vampirised’. The minute you have an idea some asshole from the New York Times writes about how cool it is and that’s the end of it.

Yeah, it’s true.

But you know we’re in a stage now of cultivating our own gardens. There aren’t any great community movements. There isn’t an avant-garde. There isn’t a bohemia. But there are interesting individuals building private worlds everywhere, and you have to be lucky enough to get to know them. That’s what my life is like now. I know some really interesting people in Berlin, a couple in Paris, a handful in New York. Bohemia now is about travelling: it’s people on the move all the time. Two months here, three months there, a month in Europe, a month on the west coast, two months in New York: Bohemia is a moveable show. It always was a moveable show; remember Jack Kerouac, On the Road. The only way to sustain bohemianism is by moving - and here I am with my gorgeous apartment.

Let’s bring it back to you and your apartment - which is beautiful and comfortable.

Bohemia isn’t usually the final stop of an artist. It’s usually a youthful thing. It’s the lifestyle you have while you become an artist, not necessarily the lifestyle you have as an artist. Age has to do with it. There are different kinds of comfort. One kind happens in places like Berkeley, where they formed block associations and protected their property. I believe I have another kind of comfort, which is just an attractive wall between me and the cold weather outside. You know what I mean? I’m not going to form a block association. I don’t think of my living space as integrated into the social fabric. It’s just my fantasy world. It has to do with the values of Technicolor film and how those colours excite me. It’s fantasy. I’m living a fantasy world. I’m not trying to impress a culture. For me it’s not, ‘Wow, wait till people see it and I have dinner parties. It’ll give me status in my community’. Fantasy’s important to me; I want to live in a Dr. Seuss story. It’s how I make myself feel emotionally. It’s a personal aesthetic experience, not a social gesture. The apartment isn’t fashionable or - my least favourite word - ’chic’. The bright, clashing colours go against every interior de- sign trend that’s happen- ing at the moment.

You’re right, and that’s why fantasy, personal fantasy is the thing that you should stress.

In other words I’ve reached an age where I don’t want to deal with the world. I want to do my work, and I want an environment that makes me smile.

Yeah, and visit friends around the world living the same way.

Yeah, it’s like a worldwide network of fantasy that’s ignoring the way things are congealing. But think about what happened after the fall of Rome, before the renaissance. That was like an enormous bohemia too. People lived in isolated pockets; monks, the monasteries collecting enormous stockpiles of culture that had very little connection to the world at the time, because it was the dark ages all around them. In a way it’s like that now. I’m a monk collecting culture for my own purposes - and for the future.